There are various rules governing the use of French and English within the Canadian judicial system. This Background Paper focuses on the federal government's role in the matter, looking particularly at the issues relating to bilingualism within the Canadian court system.

There are a number of different acts that govern the administration of justice in the two official languages, including the Constitution Act, 1867, Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and Official Languages Act. In addition to these constitutional and legislative obligations, there are a number of other acts and regulations that establish specific criteria for the respect of the official languages by federal courts.

Canada's justice system is both bilingual and bijural, and federal courts are called on to interpret legislation that reflects these realities. The French and English versions of federal legislation have equal force of law and are co‑drafted such that they are of equal value.

The very nature of the operations of federal courts accords an important place to the use of French and English, with respect to submissions as well as communications and proceedings. In order to permit litigants to exercise their language rights, translation and simultaneous interpretation services are offered under certain conditions.

Finally, the judgments of federal courts are made available in both official languages. However, there are still obstacles to making them available simultaneously or to ensuring that both language versions are of the same quality. The delays associated with the translation of some judgments from courts other than the Supreme Court of Canada have fed the demand to clarify the obligations arising from the Official Languages Act.

Criminal law is a special case, because the use of official languages is governed by the Criminal Code. Under that code, the accused is entitled to a trial in the official language of his or her choice anywhere in Canada and is entitled to have the indictments and criminal information translated. This requires courts that deal with criminal affairs to be institutionally bilingual.

Despite the existing obligations, full implementation of judicial bilingualism is still not assured. The appointment of bilingual judges, both in the superior courts and provincial and territorial courts of appeal as well as in the Supreme Court of Canada, provokes numerous debates.

In recent years, the federal government has taken measures to compensate for the lack of bilingual capacity in the federal judiciary. Despite these measures, there is increasing pressure to make legislative changes to achieve a bilingual judiciary. The debates on the modernization of the Official Languages Act were an opportunity to focus on the current challenges and what is still to be done to ensure equal access, for all Canadians, to a justice system in both official languages.

The right to be heard in the official language of one's choice without the use of an interpreter has already been fueling parliamentary debates for several years. Offering language training to all justice professionals and assessing their language abilities form part of the solutions envisaged to improve equitable access to the justice system. Improvements were also made, during the 42nd Parliament, to the protection of language rights in the criminal law and family law sectors.

Access to justice in both official languages is an issue that calls directly for cooperation between the federal and provincial governments and all actors in the justice system. The federal government is also aware of the challenges to be met in this area and, for more than a decade and a half, has offered funding to increase networks' capacities, improve training and facilitate access to justice services in both official languages. The objective is to ensure equal access to services of equal quality for francophones and anglophones in Canada. Some would like to see this take the form of a well‑defined legislative obligation.

The rules governing bilingualism in the Canadian court system will continue to evolve in the years to come in response to case law, legislative changes and changing attitudes within Canadian society. The debates on the modernization of the Official Languages Act – a bill to achieve this end is slated to be tabled by the end of the 43rd Parliament – will be an opportunity to debate these issues.

This Background Paper explores the rules that govern the use of both official languages in Canada's justice system, with particular focus on the role of the federal government. First, it provides an overview of Canada's court system, followed by an examination of the legislative and constitutional framework of bilingualism in the federal context, both in federal courts and in the criminal law. Lastly, it looks at some current issues related to the use of both official languages in Canada's court system.

Canada's court system is made up of courts that are administered either by the federal government or by the provincial and territorial governments.

Administrative tribunals1 – at both the federal and provincial/territorial levels – are not part of the court system as such. However, they play an essential role in examining matters that are subject to a wide variety of administrative rules and regulations, and they may be called upon to make rulings on language rights issues. They can also refer cases to superior courts, if necessary. Since 2014, the Administrative Tribunals Support Service has been providing support services to federal administrative tribunals.

With the exception of Nunavut,2 each province or territory has three levels of court:

The three levels are administered by the relevant province or territory. That said, the federal government is responsible for appointing judges to provincial superior courts and courts of appeal, as well as to the Supreme Court of Yukon, the Supreme Court of the Northwest Territories and the Nunavut Court of Justice.4

Parliament has created specialized courts to handle cases in specific areas of the law: the Tax Court of Canada, the military courts and the Court Martial Appeal Court are examples of these specialized federal courts. Parliament has also established the Federal Court and the Federal Court of Appeal. Both of these courts have civil jurisdiction, but they deal only with cases that are subject to federal statutes. Since 2003, the Courts Administration Service has provided support services to all federal courts.

The highest court in the land is the Supreme Court of Canada. It is the final court of appeal, and its jurisdiction covers all areas of the law. The Supreme Court also hears cases that involve a question of significant public interest or raise an important issue of law. Additionally, the Supreme Court may be called upon to advise the federal government regarding the interpretation of the Constitution and federal or provincial legislation.

The federal government is responsible for appointing judges to all federal courts. In the case of Supreme Court justices, candidates are reviewed by an independent advisory board and appointed by the Prime Minister. With respect to judges of the Federal Court, Federal Court of Appeal and Tax Court of Canada, candidates are reviewed by advisory committees and appointed by the Governor General acting on the advice of the federal Cabinet, upon the recommendation of the Minister of Justice (puisne judges) or the Prime Minister (Chief Justices and Associate Chief Justices).5

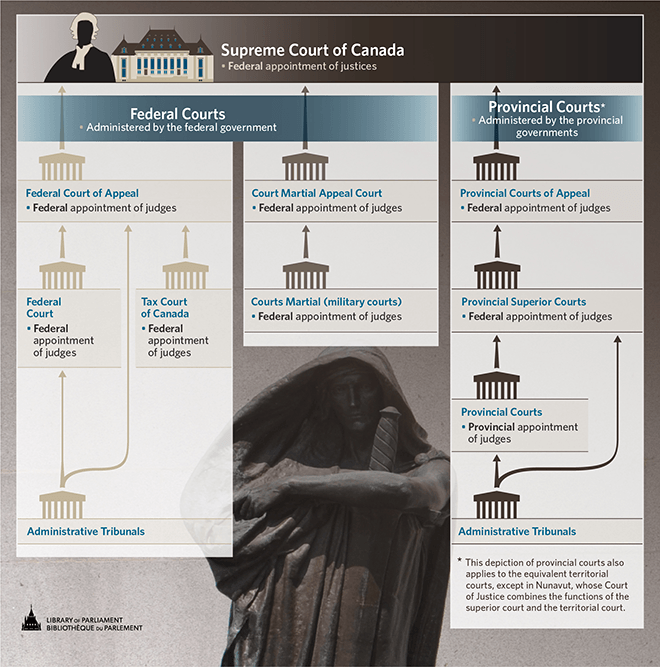

Figure 1 depicts the overall structure of Canada's court system and the federal government's authority to appoint judges, an issue that will be discussed in more detail in section 4.1 of this Background Paper.

Figure 1 – Canada's Court System and Responsibility for the Appointment of Judges

The infographic illustrates the general structure of the Canadian court system and the authority for appointing judges.

At the top is the Supreme Court of Canada, whose justices are appointed at the federal level.

Then comes, on one side, federal courts, which are administered by the federal government, which appoints the judges to these courts, and, on the other side, the provincial courts, which are administered by the provincial governments, which appoint the judges for these courts, except for the superior courts and courts of appeals, whose judges are appointed by the federal government.

The federal courts include the administrative tribunals, the Federal Court and the Canadian Tax Court, as well as the Federal Court of Appeal.

The Courts Martial and the Court Martial Appeal Court of Canada are also federal courts.

On the provincial side are the administrative tribunals, the provincial courts, the superior courts and the courts of appeal.

The description of the provincial courts also applies to the territorial courts, except for Nunavut, where the functions of the Court of Justice combine those of the superior court and the territorial court.

Sources: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from Department of Justice, Canada's Court System; Canadian Superior Courts Judges Association, Structure of the Courts; Office of the Commissioner for Federal Judicial Affairs Canada, Guide for Candidates, October 2016; and National Defence Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. N‑5.

This section examines the language requirements that must be met by the federal courts, with a focus on a few key principles.

Various pieces of legislation provide for the administration of justice in both official languages. Table 1 summarizes the main legislative and constitutional requirements that apply to the federal courts with regard to official languages.

|

Constitution Act, 1867 |

Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms |

Other Legislation |

|---|---|---|

|

Section 133 guarantees that both English and French can be used "in any Pleading or Process" before the courts of Canada (and Quebec). Furthermore, section 133 stipulates that the Acts of the Parliament of Canada and of the Legislature of Quebec must be printed and published in both languages. |

Section 14 grants the right to the assistance of an interpreter during proceedings. Section 16 states that English and French are the official languages of Canada and includes the principle, "to advance the equality of status or use of English and French." Section 19 establishes that either English or French may be used by any person in, or in any pleading in or process issuing from, any court established by Parliament (and any court of New Brunswick). |

In addition to these general provisions, a number of Acts and regulations establish specific criteria with respect to official languages:

|

|

Official Languages Act |

||

|

Part II: Language Requirements for Legislative Instruments

|

||

|

Official Languages Act |

||

|

Part III: Language Requirements for the Administration of Justice

|

||

The Canadian legal system is based on two legal traditions: the civil law tradition, which applies in Quebec, and the common law tradition, which applies in the rest of Canada. While the Federal Court and the Federal Court of Appeal only hear cases that are subject to federal statutes, the Supreme Court can be called on to interpret legislation from either of these two legal traditions.

Federal courts interpret laws that are conceived, drafted and adopted in both official languages. Both language versions are equally authoritative.

Federal legislation is drafted simultaneously in both English and French, and both versions are equally authoritative. The requirements set out in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (Charter)6 and the Official Languages Act (OLA)7 mean that most federal legislation is co‑drafted (written in parallel) in both languages, rather than written in one language and then translated into the other. Common sense must govern the interpretation of bilingual laws, according to Karine McLaren, former Director of the University of Moncton's Centre de traduction et de terminologie juridiques, because the English and French versions of a law express the same concepts:

There may be two language versions of a law, but there can only be one intention of the legislator, and therefore one standard, which applies universally regardless of the language in which the law is read.8

The use of official languages in the Canadian justice system depends on the type of court and the nature of the case. As Vanessa Gruben of the University of Ottawa says:

The federal government has the authority to regulate the language used before federal courts and in relation to criminal procedure. … Parliament also has the authority to legislate language usage in certain administrative tribunals.9

The right for everyone to use his or her language of choice before federal courts extends to litigants, lawyers, witnesses, judges and other officers of the court.

In federal courts, the right to use English or French is decided based on various factors and extends to all participants in the justice system, depending on the circumstances.

Language requirements apply to all written submissions (e.g., summonses) in addition to submissions of the parties, oral submissions, statements and briefs. They do not apply to evidence.

Verbal and written communications in federal courts can be in English or French. Section 133 of the Constitution Act, 1867 enshrines the right to use either language in any pleading or process. This requirement is echoed both in the Charter – which alludes to the right to use English and French in cases and proceedings – and in the OLA.

Translation and simultaneous interpretation services are offered under certain conditions to ensure that language rights are respected.10 The right to the assistance of an interpreter during proceedings is guaranteed by the Charter. However, a distinction must be made between the language rights of the accused (i.e., the right to express oneself in one's own language) and the right to a fair trial (i.e., the right to understand and be understood). In 1999, the Supreme Court summarized this distinction in R. v. Beaulac:

The right to a fair trial is universal and cannot be greater for members of official language communities than for persons speaking other languages. Language rights have a totally distinct origin and role. They are meant to protect official language minorities in this country and to insure the equality of status of French and English.11

The OLA provides for translation services on request for court documents. The provisions regarding simultaneous interpretation are mainly to allow witnesses to express themselves and to be heard without prejudice in the language of their choice.

Where a federal institution is a party to a civil case, the OLA requires the institution to use the official language chosen by the other parties or the one that makes the most sense in the circumstances.

In general, the judgment in a trial is delivered and issued in the language in which the trial was conducted. A translation of the judgment must be made available to the public as soon as possible. A decision delivered in only one language is not considered invalid as long as it respects the provisions of the OLA.

Federal judgments are published simultaneously in both official languages in either of the following situations:

The same standards apply to decisions published in the official reporters.

Karine McLaren makes the following observations with regard to translating decisions:

Section 20 of the Official Languages Act does not impose a specific process on the various federal courts. As a result, they have come up with different ways to meet their respective obligations.12

She adds that no objective criteria have been established to determine what is of general public interest or importance with regard to which decisions to translate.13 However, the need to establish such criteria had already been raised by Official Languages Commissioner at the time, Victor Goldbloom, in 1999.14

Furthermore, no sanctions are provided to address delays in the translation and publication of decisions. According to Vanessa Gruben, severe sanctions for failure to comply with this obligation would enhance equal access to the justice system in both official languages.15 Former law professor Michel Doucet adds that the statutory requirement to translate a decision does not imply recognition of the equal authority of both versions, since no federal courts other than the Supreme Court have established procedural rules to this effect.16

There is some dispute over whether the obligation to publish judgments on the web in both official languages simultaneously flows from Part III of the Official Languages Act, which deals with the administration of justice, or from Part IV, which covers communications with the public. This ongoing dispute is compromising equal access to the judgments of federal courts in both official languages.

While the Supreme Court publishes all its decisions in both languages simultaneously, the same cannot be said for the other federal courts, which translate their decisions "as soon as possible." Complaints have been lodged with the Courts Administration Service (CAS) with regard to the language in which decisions of the Federal Court, the Federal Court of Appeal and the Tax Court of Canada are posted. The then‑Official Languages Commissioner, Graham Fraser, who began investigating this issue in 2007, submitted a report to the Governor in Council in 2016 as well as a report to Parliament.17 In his opinion, the ongoing disagreement over how to interpret the obligations related to the language of posted decisions requires either legislative clarification or a reference to the Supreme Court.

The House of Commons Standing Committee on Official Languages studied the matter and tabled a report in December 2017, in which it recommended that the federal government clarify the obligations under the OLA as follows:

Moreover, in its 2017 budget, the federal government acknowledged that there were problems with accessing decisions in both English and French, and it provided the CAS with an additional $2 million over two years starting in 2017–2018 to increase its translation capacity.19 Starting in 2019–2020, the CAS was given $1.7 million/year in permanent funding to that end. The organization modified its translation model by focusing on the use of an automated translation tool.20

During the debates on the modernization of the OLA, experts from the justice sector asked that section 20 be clarified to make it obligatory to translate a larger number of legal judgments and publish them simultaneously on the web.21 This led the Senate Standing Committee on Official Languages to recommend, in its final report published in June 2019, that the OLA be amended in order to:

The current Commissioner of Official Languages, Raymond Théberge, presented similar recommendations on amending the OLA to ensure easier and quicker access to federal courts' judgments in both official languages and specify the obligation to publish them simultaneously in both official languages.23 A case was brought in Federal Court in April 2018 regarding publication delays and the quality of the translation of federal court judgments, but the case was withdrawn following the applicant's death.24

The Supreme Court, the Federal Court of Appeal, the Federal Court and the Tax Court of Canada set their own rules regarding the use of either of the official languages, subject to approval by the Governor in Council. These rules of procedure must be bilingual. Section 17 of the OLA grants the Governor in Council the authority to establish such rules for the other courts, but this authority has never been exercised.

Strictly speaking, the federal courts do not have jurisdiction over criminal law,25 given that such jurisdiction lies with the provincial and territorial courts and superior courts. Language rights in criminal law are guaranteed by the Criminal Code (Code),26 as opposed to the Constitution or the OLA. Table 2 summarizes the key language requirements in criminal matters.

|

Criminal Code |

|---|

|

Section 530 guarantees the accused the right to be tried by a judge in the official language of his or her choice. The accused must be advised of this right. Certain circumstances may warrant a trial in both languages. Section 530.01 gives the accused the right to obtain from the prosecutor a translation of the portions of an information or indictment against the accused that are written in the official language that is not that of the accused. Section 530.1 outlines the circumstances under which a bilingual trial is permitted. Section 849(3) states that any pre‑printed portions of a form set out in the Code must be printed in both official languages. |

One of the unique features of th Code is that the accused has the right to be tried in the official language of his or her choice, regardless of location in Canada, and to be informed of that right. The application will automatically be accepted if the accused submits it within the prescribed time limit. If the time limit is exceeded, the court may still grant the request, if it is in the interest of justice.

All the criminal courts of Canada are subject to the language requirements outlined in the Code. The Supreme Court ruled on the application of these provisions in R. v. Beaulac:

Section 530(1) creates an absolute right of the accused to equal access to designated courts in the official language that he or she considers to be his or her own. The courts called upon to deal with criminal matters are therefore required to be institutionally bilingual in order to provide for the equal use of the two official languages of Canada.27

The administration of courts must ensure that a case can be heard in either of the official languages. It is not necessary for every person sitting on the bench to be bilingual.

A criminal trial can therefore be conducted entirely in one language, which requires courts to be institutionally bilingual.

In 2015, the Court of Appeal for Ontario, in R. v. Munkonda, handed down a decision identifying two principles governing the conduct of a bilingual trial or preliminary inquiry as follows:

Like the OLA, the Code provides for the use of translation services for indictments and criminal information.

The coming into force of section 533.1 of the Code in 2008 made it mandatory for a parliamentary committee to undertake a comprehensive review of the provisions and operation of Part XVII (Language of Accused) of the Code. This review was conducted by the House of Commons Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights, which tabled its findings in April 2014.29 One of the Committee's recommendations was that this part of the Code be re‑examined by a parliamentary committee in another five years.

Since 2019, the accused may, regardless of the type of infraction, choose to be tried in either English or French from the moment he or she appears to set the trial date.30

Some of the current issues involving the use of official languages in Canada's court system include judicial appointments; the distinction between the right to be heard and the right to be understood in the language of one's choice; access to justice; language training; and the equality of both official languages. All of these issues are discussed below, with a particular focus on the role of the federal government. A number of them require cooperation between the federal and provincial governments, which is why some of the examples used are provincial.

The federal government is responsible for appointing judges to federal courts, in addition to the superior courts and courts of appeal in the provinces and territories.

The Judges Act, the Federal Courts Act and the Tax Court of Canada Act outline the appointment process for federal judges. The Office of the Commissioner for Federal Judicial Affairs Canada is responsible for the administration of the appointments process.

Judicial Advisory Committees (JACs) are tasked with assessing the qualifications of individuals who apply for federal judicial appointment. There are a total of 17 JACs: three for Ontario, two for Quebec, one for each of the other provinces and territories, and one for the Tax Court of Canada. As of October 2016, these committees must reflect the diversity of the Canadian population, including with respect to the representation of "members of linguistic minority communities."31

Once the list of candidates has been established, the Minister of Justice presents it to the federal Cabinet and the appointments are made. The Prime Minister appoints chief justices and associate chief justices.

Candidate assessments are valid for a period of two years. "Professional competence and overall merit are the primary qualifications for judicial appointment."32 Bilingualism is one of the factors considered in assessing candidates. The composition of the pool of candidates, meanwhile, should be reflective of the diversity of the Canadian population, including members of linguistic minorities.33

Without further training:

Bilingualism is not a mandatory requirement for appointment to provincial or territorial superior courts or courts of appeal. That said, as of October 2016, candidates for judicial appointment must answer four language‑related questions as part of the application process. The federal government compiles the responses and provides the public with an overview of candidates' language proficiency, based on information gathered through self‑identification.

Of the 74 candidates appointed to superior courts of first instance between October 2016 and October 2017:34

The following year, between October 2017 and October 2018,37 there was a slight drop in language abilities of candidates compared with the previous year. Among the 79 candidates named to the bench:

Given that candidates may respond in the affirmative to any – or all – of the questions on the four language abilities, it is difficult to obtain a clear picture of the situation. Furthermore, it is impossible to say with certainty how many of the 1,107 federally appointed judges in the provinces and territories as of 1 November 202038 are bilingual. This is because:

For years, stakeholders have been calling on the federal government to appoint a sufficient number of bilingual judges to the courts administered by the provinces. Successive official languages commissioners have spoken out many times about this issue, with the most recent being Graham Fraser. In August 2013, a study into the shortage of federally appointed judges capable of hearing cases in both official languages was released by his office, in partnership with the then commissioner of Official Languages for New Brunswick, Katherine d'Entremont, and the French Language Services Commissioner of Ontario at the time, François Boileau.40 The study concluded that the existing process did not ensure the appointment of a sufficient number of bilingual superior court judges in each province and territory.

In September 2017, the federal government launched its Action Plan – Enhancing the Bilingual Capacity of the Superior Court Judiciary, in which it committed to the following:

Without further training:

In 2018–2019, the Office of the Commissioner for Federal Judicial Affairs set up a quality‑control tool to assess the second‑language abilities of judicial candidates.42 In 2020–2021, the tool will be used for all candidates who declare themselves bilingual.43

The federal government has therefore recognized the importance of appointing more bilingual judges to the superior courts of the provinces and territories, although some believe it should go even further. In its report tabled in December 2017, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Official Languages recommended that the federal government amend the Judges Act44 as follows:

Bill C‑381,46 which received first reading on 31 October 2017, had similar objectives. The bill died on the Order Paper.

During the debates on modernizing the OLA, stakeholders called for legislative improvements to enshrine the linguistic obligations of federally appointed judges.47 In its final report, the Senate Standing Committee on Official Languages acknowledged that a new version of the OLA should guarantee equal access to justice in French and English when judges are appointed to the provincial and territorial superior courts and courts of appeals. In practical terms, this means giving the Office of the Commissioner for Federal Judicial Affairs the mandate to systematically assess the need in terms of bilingual candidates for the judiciary throughout Canada and the language abilities of those candidates.48

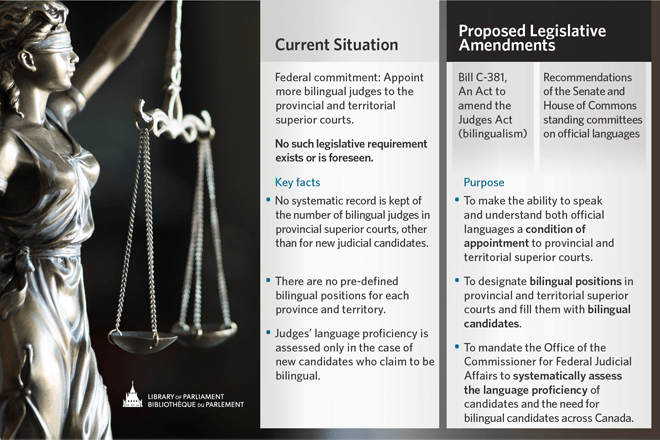

Figure 2 illustrates the difference between the current situation and the legislative measures proposed by Bill C‑381 and the reports of parliamentary committees to promote the appointment of a greater number of bilingual judges to the provincial and territorial superior courts and courts of appeals.

Figure 2 – Proposed Legislative Amendments to Increase the Number of Bilingual Judges Appointed to Provincial and Territorial Superior Courts

The infographic compares the current situation to proposed legislative amendments to promote the appointment of more bilingual judges to the provincial and territorial superior courts.

The federal government is committed to appointing more bilingual judges in these courts, but no legislative obligation is foreseen in this respect.

Currently, except in the case of new judicial candidates, there is no accounting of the number of bilingual judges in provincial superior courts.

There are no predefined bilingual positions for each province and territory.

Judges’ language abilities are evaluated in the case of new candidates who self‑declare as bilingual.

Bill C‑381, which sought to amend the Judges Act, and the recommendations of the standing committees on official languages of the House of Commons and Senate proposed legislative solutions to fill the current gaps.

The goal of the proposed legislative amendments was to make the ability to speak and understand both official languages a condition for appointment to the provincial and territorial superior courts; to designate bilingual positions within these provincial and territorial superior courts and to staff these positions with bilingual candidates; and to give the Office of the Commissioner for Federal Judicial Affairs the mandate to systematically assess candidates’ language abilities and the need for bilingual candidates in every region of the country.

Sources: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from Department of Justice Canada, Action Plan: Enhancing the Bilingual Capacity of the Superior Court Judiciary ![]() (729 KB, 1 page), 2017; Bill C‑381, An Act to amend the Judges Act (bilingualism), 1st Session, 42nd Parliament; House of Commons, Standing Committee on Official Languages, Ensuring Justice Is Done in Both Official Languages

(729 KB, 1 page), 2017; Bill C‑381, An Act to amend the Judges Act (bilingualism), 1st Session, 42nd Parliament; House of Commons, Standing Committee on Official Languages, Ensuring Justice Is Done in Both Official Languages ![]() (5.3 MB, 74 pages), Eighth Report, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, December 2017; and Senate, Standing Committee on Official Languages, Modernizing the Official Languages Act: The Views of Federal Institutions and Recommendations

(5.3 MB, 74 pages), Eighth Report, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, December 2017; and Senate, Standing Committee on Official Languages, Modernizing the Official Languages Act: The Views of Federal Institutions and Recommendations ![]() (5.5 MB, 98 pages), Final Report, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, June 2019.

(5.5 MB, 98 pages), Final Report, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, June 2019.

The Official Languages Act stipulates that "if both English and French are the languages chosen by the parties" … the judge hearing the case must be "able to understand both languages without the assistance of an interpreter." (Official Languages Act, s. 16(1)(c))

Since 1988, the OLA has included a requirement for judges of the Federal Court, the Federal Court of Appeal and the Tax Court of Canada to understand the official languages (section 16), and has recognized the authority of the Governor in Council to establish related procedural rules (section 17). That said, this language requirement is not systematically applied to all judges who are appointed, but only to those who hear cases in both languages: the principle of institutional bilingualism applies. It is impossible to determine how many of the 93 federally appointed judges sitting in those three courts as of 1 November 202049 are functionally bilingual. The appointment of more bilingual judges to any of these three federal courts has not been flagged as a concern in recent years.

The Supreme Court is governed by the Supreme Court Act (SCA),50 which does not include any provisions on official languages. Unlike the other federal courts, the Supreme Court is not subject to the provisions of sections 16 and 17 of the OLA.51

The Court has certain unique features resulting from a variety of geographical and administrative rules and conventions. Section 6 of the SCA outlines certain conditions regarding Quebec representation: at least three justices must be from the province. Convention has it that, of the remaining six justices, three come from Ontario, one from the Atlantic provinces and two from the Western provinces. The nine Supreme Court justices hold office until they reach the age of 75, but can be removed by the Governor General at the request of the Senate and the House of Commons for incapacity or misconduct.

The justices of the Supreme Court are called on to interpret statutes based on both civil and common law, and to make rulings on cases that were argued in the lower courts in either of the official languages. The Rules of the Supreme Court of Canada state that a party may use either English or French in any oral or written communication with the Court, and that simultaneous interpretation services must be provided during the hearing of every proceeding.52

The idea of appointing more bilingual judges to the Supreme Court has been the subject of much discussion in recent years. Moreover, in August 2016, a new process was established that involves an independent advisory committee mandated to provide the Prime Minister with a short list of candidates for appointment to the Supreme Court. The government has committed to appointing "functionally bilingual"53 judges. As stated by the FJA,

[t]he Supreme Court hears appeals in both English and French. Written materials may be submitted in either official language and counsel may present oral argument in the official language of their choice. Judges may ask questions in English or French. It is expected that a Supreme Court judge can read materials and understand oral argument without the need for translation or interpretation in French and English. Ideally, the judge can converse with counsel during oral argument and with other judges of the Court in French or English.54

The FJA now assesses candidates' level of functional bilingualism in the official languages. The chosen candidate then participates in a meeting with representatives of Parliament, providing them with an opportunity to ask questions about his or her candidacy, in the official language of their choice. Three bilingual judges have been appointed to Canada's highest court since this new process came into effect: Justice Malcolm Rowe, Justice Sheilah Martin and Justice Nicholas Kasirer.

The Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights studied the process leading to the appointment of Justice Rowe. It tabled its findings in February 2017, but did not make any specific recommendations regarding the appointment conditions related to bilingualism or the process for assessing the language skills of the appointee.55 In its response to the Committee's report, the government reaffirmed its commitment "to only appoint functionally bilingual candidates to the Supreme Court."56 In July 2017 and in April 2019, the government filled another vacancy on the Supreme Court, again following the appointment process established in 2016.57

In its report released in December 2017, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Official Languages called on the federal government to table a bill "guaranteeing that bilingual judges are appointed to the Supreme Court of Canada," and to amend section 16(1) of the OLA "so that the requirement to be able to understand both official languages also applies to judges of the Supreme Court of Canada."58 Commissioner of Official Languages Raymond Théberge supported this proposal in his recommendations on the modernization of the OLA.59 The suggestion was also part of the summary of public consultations conducted by the federal government.60

For its part, after hearing multiple witnesses asking for legislative amendments to that end, the Senate Standing Committee on Official Languages, in its final report, recommended amending the OLA and any other federal act "to require that, on appointment, judges of the Supreme Court of Canada have a sufficient understanding of English and French to be able to read the written submissions of the parties and understand oral arguments without the assistance of translation or interpretation services." 61

Several private members' bills have been tabled in the House of Commons since 2008 with a view to requiring Supreme Court justices to understand both official languages.62 These bills have proposed two different approaches:

The debate surrounding the appointment of Justice Marc Nadon in 2013, and the ensuing reference to the Supreme Court, raised questions about imposing bilingualism as a condition of appointment for Supreme Court justices, which some consider unconstitutional. This reference stated that Parliament "cannot unilaterally modify the composition or other essential features of the Court."69 It did not, however, clarify whether the addition of language requirements constitutes a modification of the essential features of the Supreme Court. The parliamentary official languages committees referred to this issue in different reports.70 David Lametti, the Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada, also stated that such a measure might be unconstitutional and represent an obstacle to the appointment of Aboriginal judges.71

Figure 3 below highlights the differences between the two approaches studied by Parliament thus far to promote the appointment of more bilingual judges to the Supreme Court.

Figure 3 – Proposed Mechanisms to Promote the Appointment of More Bilingual Judges to the Supreme Court

The infographic compares two proposed mechanisms for appointing more bilingual judges to the Supreme Court.

The first option provides for an amendment to the Supreme Court Act, as exemplified by Bill C‑203, An Act to amend the Supreme Court Act (understanding the official languages), which was introduced in 2015 and defeated in the House of Commons on 25 October 2017.

The goal of this bill was to make understanding of both official languages, without an interpreter, a condition for appointing judges to the Supreme Court, thus making personal bilingualism for justices obligatory.

The effect would have been to target the language abilities of every judge appointed, to make bilingualism mandatory for all nine justices and to make it impossible to appoint a judge who did not have the required language abilities.

This requirement would not, however, have applied to the justices currently on the court.

Three similar bills were tabled between 2018 and 2013: Bill C‑559, Bill C‑232 and Bill C‑208.

The goal of second option was to amend the Official Languages Act, as exemplified in Bill C‑382, An Act to amend the Official Languages Act (Supreme Court of Canada), which was introduced in the House of Commons on 31 October 2017 and died on the Order Paper.

The goal of this bill was to impose an obligation at the level of the Supreme Court of Canada that justices be able to understand both official languages, without an interpreter, by imposing institutional bilingualism on the Supreme Court.

It would have focused on the language abilities of the justices who hear cases, allowed the appointment of a judge who does not have the necessary language abilities (but prevented them from hearing a case in a language they cannot understand without an interpreter) and allow bilingual cases to be heard by a reduced number of justices.

Since a minimum of five justices is required to hold a session of the Supreme Court, only five bilingual justices would be necessary.

A similar bill was introduced in 2008, Bill C‑548.

Sources: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from Bill C‑203, An Act to amend the Supreme Court Act (understanding the official languages), 1st Session, 42nd Parliament; and Bill C‑382, An Act to amend the Official Languages Act (Supreme Court of Canada), 1st Session, 42nd Parliament.

Does the right to use the official language of one's choice imply the right to be understood in that language without the use of an interpreter?

In 1986, the Supreme Court ruled in MacDonald that parties have the right to use either language, but that this does not necessarily give them the right to be heard or understood by the court in that language.72 However, the broad and liberal interpretation of language rights by the courts that followed appears to run counter to this decision on the right of both parties and judges to use the language of their choice.

When the OLA was enacted in 1988, Parliament imposed on federal courts (with the exception of the Supreme Court) a requirement to ensure that judges understand, without the assistance of an interpreter, the official language in which the trial is being conducted. A unilingual judge can hear a case if he or she understands the language chosen by the parties. When the case is heard in both languages, the designated judge must be bilingual. As of the coming‑into‑force of that requirement in 1993, federal courts must ensure that there are enough judges capable of hearing cases in either of the official languages.

In March 2011, the Provincial Court of Alberta made a ruling in Pooran that stated the following:

If litigants are entitled to use either English or French in oral representations before the courts yet are not entitled to be understood except through an interpreter, their language rights are hollow indeed. Such a narrow interpretation of the right to use either English or French is illogical, akin to the sound of one hand clapping, and has been emphatically overruled by Beaulac.73

The authors of a study into whether there is a right to be understood directly, orally and in writing, without the assistance of an interpreter or translator, in the specific context of the Supreme Court, concluded that there are numerous grounds for courts to conclude that the right to be understood directly by the judges of the highest court does indeed exist.74

The lack of lawyers and judges who have a sufficient understanding of English and French is one of the primary obstacles to accessing justice in the official language of one's choice. Other difficulties include institutional obstacles, such as a lack of bilingual legal staff, a lack of bilingual legal or administrative resources, and the delays associated with choosing to proceed in one language rather than the other.

Access to justice in both official languages requires cooperation between the federal and provincial governments. Despite the legislative and constitutional requirements in place, there are still limitations to accessing the courts in one's official language of choice. While many of the provinces and territories have legislative provisions that promote access to justice in both official languages,75 work remains to be done to ensure that everyone has equal access to justice in both languages across the country.

A study conducted on behalf of Justice Canada in 2002 showed that the judicial and legal services offered in both official languages vary greatly across the country.76

Since 2003, the federal government has offered additional funding to increase access to justice in both official languages through four horizontal initiatives. First, the Action Plan for Official Languages (2003–2008) provided $18.5 million over five years to target the following areas:

Another initiative was the Roadmap for Canada's Linguistic Duality 2008–2013,78 which earmarked $41 million over five years to pursue the initiatives above and to encourage young people who are fully bilingual to pursue a career in the field of justice. It also provided for intensified linguistic training efforts for all officers of the court (e.g., court clerks, stenographers, justices of the peace and mediators).

The Roadmap for Canada's Official Languages 2013–201879 budgeted $40.2 million over five years for training, networks and access to justice services.

Finally, the current Action Plan for Official Languages 2018–2023 contains financial commitments of $103.55 million over five years: the original $40.2 million for networks, training and access to justice services, an additional $49.6 million for the Contraventions Act Fund, an extra $10 million for the Access to Justice in Both Official Languages Support Fund, and $3.75 million in core funding for justice sector community organizations.80

In the study he released in August 2013 in partnership with his provincial counterparts, the then commissioner of Official Languages of Canada confirmed that the bilingual capacity of the judiciary was not guaranteed at all times and that this failure could lead to significant additional delays and costs.81 The study recognized that rectifying the situation would require coordinated action on the part of the federal Minister of Justice and his or her provincial and territorial counterparts, as well as the chief justices of the superior courts. Of the 10 recommendations, which were addressed to both the federal Minister of Justice and his provincial and territorial counterparts, four were aimed at strengthening intergovernmental collaboration. The Commissioner addressed the issue once again in his 2015–2016 annual report, given that there had been no follow‑up on any of the 10 earlier recommendations.82

The federal government's 2017 action plan to enhance the bilingual capacity of the superior court judiciary responds to some of the recommendations of the Commissioner of Official Languages in that it encourages the Department of Justice Canada to do the following:

During the debates on the modernization of the OLA, stakeholders asked for legislative changes to clarify the federal objectives on access to justice in both official languages, including the importance of intergovernmental cooperation and Justice Canada's responsibilities in this regard.84 Neither the parliamentary committees nor the Commissioner of Official Languages responded to these requests with formal recommendations.

Changes made to the Divorce Act in June 2019 will, when they come into force, extend the right to access to family justice in the language of one's choice to all Canadian litigants.85 The Department of Justice has been given a budget of $21.6 million over five years, beginning in 2020–2021, to work in cooperation with the provinces and territories to implement these new provisions.86

Language training is another area that calls for cooperation between the federal and provincial governments. Since 1978, the federal government has offered language training to federally and provincially appointed judges through the FJA so that they can improve their second language skills. Through the Judges' Language Training Program,

numerous judges have gained sufficient knowledge to master a second language. Thus many of them are able to preside in court, understand testimony, read legal texts, write judgments and participate in legal conferences in their second language.87

Furthermore, the Department of Justice's Access to Justice in Both Official Languages Support Fund includes a Justice Training Component that is aimed at providing advanced training on legal terminology to bilingual justice professionals; developing a curriculum for bilingual students interested in pursuing a career in justice; setting out a recruitment and promotion strategy for legal careers; and designing linguistic training tools.

In terms of academia, the University of Moncton, the University of Ottawa and McGill University are the only post‑secondary institutions that offer law programs in both official languages. Other organizations, such as the Centre canadien de français juridique and the various associations of French‑speaking jurists, offer targeted language training to various justice professionals. These stakeholders have joined forces by creating a national justice training network (the Réseau national de formation en justice) to train post‑secondary students and people already working in the justice system and to enhance the capacity of Canada's justice system to provide access to justice in both official languages.

A report submitted to the Department of Justice Canada in 2009 concluded that being proficient in the legal vocabulary of each language is essential to ensure institutional bilingualism in the field of justice.88 An evaluation released by the department in May 2012 revealed that additional efforts will be needed to meet the challenges identified in that study.89 On this front, distance training could become a priority.90 Another departmental evaluation in 2017 confirms the ongoing need to support language training for all professionals involved in the justice system.91 The debates on the modernization of the OLA confirmed that there is still a crying need for training for justice officials.92

The study released in August 2013 by the Commissioner of Official Languages presented the following vision of language training for judges:

Language training should serve to maintain and enhance the court's bilingual capacity, while allowing interested judges to take advantage of the learning activities and to use their language skills within the context of their work. The current FJA language training program seems to meet judges' needs in terms of second language learning as well as maintaining and strengthening their bilingual capacity. However, the language training tools offered to provincial court judges could be useful models if FJA would like to provide a complementary language training program for superior court judges wishing to evaluate their language skills in work‑related situations.93

A French‑language training program has since been developed by the Provincial Court of New Brunswick and has even been cited as a model.94 An English‑language training project for judges was also developed in Quebec in partnership with Bishop's University. There are other training initiatives in certain regions of Canada for specific areas of legal practice. More needs to be done, however, which is why the federal government's 2017 action plan to enhance the bilingual capacity of the superior court judiciary includes measures that

In terms of assessing language proficiency, a test has been developed by the KortoJura Evaluation Service, which evolved out of the language training program for judges created by the Provincial Court of New Brunswick. This test evaluates the initial language skills of professionals in the justice system and the progress made by those participating in language training. In its December 2017 report, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Official Languages made the following recommendation:

That the Office of the Commissioner for Federal Judicial Affairs explore existing Canadian resources, such as KortoJura, to develop a language proficiency test and a scale to evaluate the language skills of candidates for appointment to the federal judiciary and the Supreme Court.96

In his 2015–2016 annual report, the Commissioner of Official Languages also recognized the importance of creating national standards and assessment tools.97 The debates on the modernization of the OLA have confirmed the need to deploy existing tools on a wider scale.98

In R. v. Beaulac, the Supreme Court of Canada stated that the purpose of sections 530 and 530.1 of the Code is to

provide equal access to the courts to accused persons speaking one of the official languages of Canada in order to assist official language minorities in preserving their cultural identity.99

Furthermore, the Court recognized that language rights are based on the principle of true equality between the two official languages:

[T]he existence of language rights requires that the government comply with the provisions of the Act by maintaining a proper institutional infrastructure and providing services in both official languages on an equal basis. … [A]n application for service in the language of the official minority language group must not be treated as though there was one primary official language and a duty to accommodate with regard to the use of the other official language. The governing principle is that of the equality of both official languages.100

"Where institutional bilingualism in the courts is provided for, it refers to equal access to services of equal quality for members of both official language communities in Canada." (R. v. Beaulac, para. 22)

The study carried out on behalf of the Department of Justice Canada in 2002 confirmed that "equal access to high quality judicial and legal services in both official languages is a contributing factor in completing the plan for a society that, in this respect, remains unfinished."101 Some have asserted that true equality means an active offer of services. In DesRochers, the Supreme Court stated, "[s]ubstantive equality, as opposed to formal equality, is to be the norm, and the exercise of language rights is not to be considered a request for accommodation."102 Moreover, in Thibodeau, the Federal Court confirmed that there are four components to the equality of the two official languages: equality of status, equality of use, equality of access and equality of quality.103

The principle of the equality of the two official languages that is recognized in Canadian case law provides for the equal treatment of the two language communities in Canada. According to Vanessa Gruben, there is every reason to believe that a broad interpretation of the principle of the equality of the two official languages could lead the courts to adjust their vision of language rights in the judicial realm.104 A 2010 impact study by lawyer Ingride Roy highlighted three principles applicable to language equality that flow from the case law:

In his August 2013 study, the Commissioner of Official Languages acknowledged that "superior court judges must be better aware of the language rights of those who appear before the courts in order to ensure substantive equality in access to justice in both official languages."106 The federal government's action plan to enhance the bilingual capacity of the superior court judiciary does not directly address this issue, but nevertheless provides certain commitments for improving respect for the linguistic rights of Canadian litigants.

The interpretation of language rights is constantly evolving. One example of this is the recent debate on bilingualism for Supreme Court justices. In 1999, the Supreme Court adopted a broad and liberal view of these rights in the legal system:

Language rights must in all cases be interpreted purposively, in a manner consistent with the preservation and development of official language communities in Canada.107 [Emphasis in the original]

This interpretation has been taken up in judgments many times in the years since. The rules that govern bilingualism in Canada's court system could evolve in the coming years due to case law, legislative amendments or changing attitudes within Canadian society.

† Library of Parliament Background Papers provide in‑depth studies of policy issues. They feature historical background, current information and references, and many anticipate the emergence of the issues they examine. They are prepared by the Parliamentary Information and Research Service, which carries out research for and provides information and analysis to parliamentarians and Senate and House of Commons committees and parliamentary associations in an objective, impartial manner. [ Return to text ]

In September 2020, the Canadian Bar Association (CBA) urged the Prime Minister and the Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada to appoint Black, Indigenous and People of Colour to the Supreme Court. In 2010, the CBA adopted a motion ![]() (269 KB, 4 pages) to amend s. 16(1) of the OLA in favour of appointing bilingual judges to the Supreme Court. In reaction to the CBA's request, the Association des juristes d'expression française de l'Ontario objected that the principle of diversity of judicial appointments was inconsistent with the principle of the bilingualism of Supreme Court judges, given that this was an essential professional competency. For an overview of the debate on bilingualism as a judicial competency, see Juan Jiménez‑Salcedo, "Le débat autour du bilinguisme des juges à la Cour suprême du Canada : analyse de la doctrine et des débats parlementaires," International Journal for the Semiotics of Law, 33, 11 May 2020, pp. 325–351; and Jean‑Christophe Bédard‑Rubin and Tiago Rubin, "Assessing the Impact of Unilingualism at the Supreme Court of Canada: Panel Composition, Assertiveness, Caseload, and Defence

(269 KB, 4 pages) to amend s. 16(1) of the OLA in favour of appointing bilingual judges to the Supreme Court. In reaction to the CBA's request, the Association des juristes d'expression française de l'Ontario objected that the principle of diversity of judicial appointments was inconsistent with the principle of the bilingualism of Supreme Court judges, given that this was an essential professional competency. For an overview of the debate on bilingualism as a judicial competency, see Juan Jiménez‑Salcedo, "Le débat autour du bilinguisme des juges à la Cour suprême du Canada : analyse de la doctrine et des débats parlementaires," International Journal for the Semiotics of Law, 33, 11 May 2020, pp. 325–351; and Jean‑Christophe Bédard‑Rubin and Tiago Rubin, "Assessing the Impact of Unilingualism at the Supreme Court of Canada: Panel Composition, Assertiveness, Caseload, and Defence ![]() (1.4 MB, 43 pages)," Osgoode Hall Law Journal, Vol. 55, No. 3, summer 2018, pp. 715–755. [ Return to text ]

(1.4 MB, 43 pages)," Osgoode Hall Law Journal, Vol. 55, No. 3, summer 2018, pp. 715–755. [ Return to text ]

© Library of Parliament