Bill C-34, An Act to give effect to the Tsawwassen First Nation Final Agreement and to make consequential amendments to other Acts, received first reading in the House of Commons on 6 December 2007. Bill C-34 was adopted without amendments by the House of Commons and the Senate on 17 June and 26 June 2008 respectively. Its enactment completes ratification of the tripartite comprehensive land claim and self-government agreement among the Tsawwassen First Nation, British Columbia and Canada, the first modern treaty to be concluded under the British Columbia Treaty Commission process, and the province’s first urban treaty.

The historic treaty process resulting in land treaties involving the surrenders of vast Aboriginal territories in Ontario, the Prairie provinces and the present Northwest Territories, was largely not entered into with British Columbia First Nations. The 14 Vancouver Island Douglas Treaties of the 1850s involved purchases of tracts from Coast Salish groups(1) totalling fewer than 400 square miles,(2) and did not serve as a precedent for further treaty-making on either the Island or the mainland.(3) The only other treaty activity involving land cessions in British Columbia occurred between 1900 and 1914, when four First Nations groups in the northeastern portion of the province adhered to Treaty 8.(4)

In concluding the Vancouver Island treaties, Governor James Douglas had recognized Aboriginal title, consistent with the principles of the Royal Proclamation of 1763.(5) However, denial of title subsequently became the enduring position taken by successive colonial and provincial policy makers.(6) After its 1871 entry into Confederation,(7) British Columbia did not subscribe to the federal government’s view that policies applied in the prairie provinces recognizing and extinguishing Aboriginal rights should extend to the province.(8) Although Aboriginal groups appealed to the federal government for larger reserves than had been allotted by the province,(9) and despite ongoing conflict between the federal and provincial governments on this issue, Ottawa did not press the province on the question of Aboriginal title or treaties.

Land-related developments over the ensuing period included the establishment, in 1912, of the McKenna-McBride Royal Commission in order to settle federal-provincial differences over Indian affairs and lands. The Commission’s terms of reference and 1916 report focused narrowly on reserve size, rather than on fundamental issues of ownership and control of land. In 1920, the federal British Columbia Indian Lands Settlement Act implemented the McKenna-McBride recommendations. In 1927, an amendment to the Indian Act that remained in effect until 1951 made it illegal for any person to accept payment from an Aboriginal person for the pursuit of land claims.(10)

In the result, as the colony/province expanded, First Nations groups lost access to and use of most of their traditional territories, while issues related to Aboriginal title in British Columbia remained largely unaddressed.

In 1968, the Nisga’a Nation initiated a court challenge seeking a declaration that Aboriginal title to the Nass Valley in northwest British Columbia had never been extinguished. Although the province’s superior courts dismissed the suit, suggesting that, even if title did exist, it had been extinguished implicitly by pre-1871 land legislation, the Supreme Court of Canada’s 1973 decision in the Calder case represented a landmark for all Aboriginal groups with outstanding claims.(12) In finding that the Nisga’a had held title prior to the creation of British Columbia, the Court confirmed that Aboriginal peoples’ historic occupation of the land gave rise to legal rights in the land that survived European settlement, thus recognizing the possibility of present-day Aboriginal rights to land and resources.

The Calder decision proved a significant factor in prompting the federal government to develop policies for addressing unsettled Aboriginal land claims. Initially released in 1973, the first “comprehensive land claims policy” was adopted in 1976,(13) and was reaffirmed in 1981 in In All Fairness: A Native Claims Policy – Comprehensive Claims.(14) In 1986, revisions to the policy allowed for a broader scope of subject matters to be negotiated within the land claim context(15) and, in 1993, the government reiterated the objective of the comprehensive claim process as being to negotiate treaties that determine ights to land and resources, “[exchanging] undefined Aboriginal rights for a clearly defined package of rights and benefits.”(16) In 1995, a policy shift occurred with the then Liberal government’s recognition of the inherent right of self-government as an existing Aboriginal right under section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982. This paved the way for the negotiation of constitutionally protected self-government rights as well as land rights in new treaties. With one exception, treaties concluded since 1995 contain governance chapters.(17)

A long-standing issue associated with comprehensive claims has been the federal policy requirement that Aboriginal groups surrender their Aboriginal rights and title to lands and resources in exchange for defined treaty rights. The dominant underlying theme has concerned the need to achieve “certainty” with respect to land and resource rights and interests. Aboriginal groups have consistently opposed this policy, which has also been viewed critically in a number of reports.(18) And while the language of cession, release and surrender typical of earlier land claim agreements has not been reiterated in more recent treaties, the matter remains a key concern for Aboriginal groups and other observers of the land claim negotiation context.

A total of 20 comprehensive land claims have been concluded since 1973,(19) including the Nisga’a Final Agreement, the first modern treaty to be negotiated in British Columbia.(20)

From 1976 through 1990, the Nisga’a and Canada negotiated on a bilateral basis, as the provincial government maintained its long-standing denial of Aboriginal title and refused to play a role in land claim negotiations. However, during the 1980s, the province became more responsive to First Nations concerns.(21) In 1989, the Premier’s Council on Native Affairs recommended that the province establish a specific process for the negotiation of land claims and, in 1990, the province – although continuing to reject Aboriginal title – agreed to join First Nations and the federal government in tripartite negotiations.

In 1991, government and First Nations parties accepted the report of the British Columbia Claims Task Force appointed by their representatives,(22) which outlined the scope and process for land claim negotiations in the province. Significantly, the then New Democratic Party government recognized Aboriginal title and Aboriginal peoples’ inherent right of self-government. Its endorsement of the Task Force Report enabled the establishment in 1992 of the tripartite BC Treaty Commission (BCTC) and six-stage treaty process(23) that remain in effect today.

Although the establishment of the BCTC process undoubtedly marked a watershed development in the vexed history of BC First Nations’ land claims, the process has faced a number of ongoing challenges. First Nations groups have expressed frustration with the perceived lack of progress at treaty tables, the protracted nature and expense of treaty talks, and the continued alienation of lands and resources while complex negotiations are taking place.(24) Other observers are also critical of the absence of concrete results(25) under and mounting costs associated with, the BCTC process.(26)

A significant percentage of BC First Nations groups are not participating at all in what they view as a flawed treaty process. Since 2006, dozens of communities that are engaged in the process have signed on to a Unity Protocol Agreement that calls for a renewed joint table mechanism to remove barriers to negotiations resulting from what the signatories view as government parties’ rigid negotiating positions in a number of key areas.(27) The BCTC has endorsed the idea of a common issues table(28) and, in December 2007, the responsible federal and provincial ministers reportedly agreed to pursue the possibility.(29)

According to the BCTC’s 2007 Annual Report, 58 BC First Nations groups are currently participating in the treaty process at 48 negotiating tables. Six groups, apart from the Tsawwassen and Maa-nulth First Nations,(30) are in negotiations to finalize treaties (Stage 5).(31) The BCTC has indicated that “while there is success at some treaty tables, there remain considerable gaps between the parties at others. In all, about 20 tables report making progress in negotiations; another 14 tables are struggling due to significant differences in positions and the remaining 24 are doing very little or nothing at the treaty table. For many First Nations these treaties do not represent their idea of true reconciliation.”(32)

This backdrop serves to underscore the significance of the successfully completed Tsawwassen First Nation Final Agreement and Maa-nulth First Nations Final Agreement for all three parties, and for the treaty process.(33)

The Tsawwassen First Nation (TFN) is among the communities that make up the Coast Salish people of the West Coast. TFN’s historical use of the waters of the Southern Strait of Georgia and the lower Fraser River and their environs for travel, fishing and hunting is well documented. Over time the TFN, like other First Nations groups in the province, experienced the loss of all but a fraction of its claimed traditional territory, which covers over 250,000 hectares.(34)

Today about half of TFN’s current membership of around 350 reside on a 290 hectare reserve, situated between the BC Ferries terminal and the Roberts Bank Superport in the Tsawwassen suburb of the Corporation of Delta, itself a suburban municipality in the southwest portion of the Greater Vancouver region of British Columbia’s Lower Mainland.

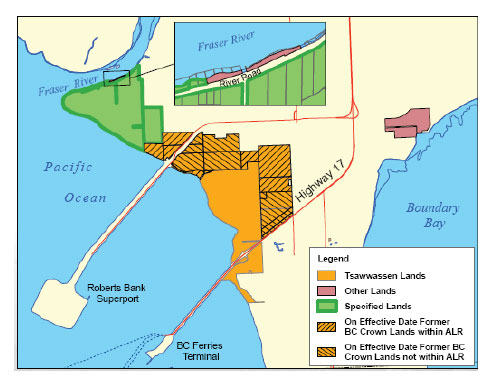

Source: Government of British Columbia, Ministry of Aboriginal Relations and Reconciliation, “Tsawwassen First Nation.”

As is the case in numerous First Nations communities, over 50% of TFN members are in the under-25 age group, while unemployment numbers are significantly higher, and annual family incomes and high school graduation rates significantly lower, than in the neighbouring non–First Nations community.(35)

TFN material documents unsuccessful petitions by community leaders dating from the 1860s – including to the McKenna-McBride Commission – to obtain a larger land base.(36) It also enumerates the gradual development and industrialization of land surrounding its reserve, and the ensuing environmental impact on TFN members and lands.

These include the development of over 16,000 hectares of surrounding land by 1890; construction and subsequent expansion of the Ferry Terminal and causeway, beginning in 1958; and construction and round-the-clock operation of the Superport, as of 1968.(37)

Residential developments on land leased from TFN include the Stahaken Development, a large subdivision leased to the Town of Tsawwassen until 2089, and the condominium complex Tsatsu Shores. About 500 non-members reside on TFN land.

The TFN entered the tripartite BCTC process in 1993 by filing its Statement of Intent to negotiate a treaty. The parties reached an agreement-in-principle that formed the basis for the final phase of negotiations in 2004 and, in December 2006, initialled the Tsawwassen First Nation Final Agreement (TFA). The TFA was ratified by 70% of registered TFN voters in July 2007 and by the Legislative Assembly of British Columbia in November 2007, with the enactment of the Tsawwassen First Nation Final Agreement Act (Bill 40).(38) The parties signed the TFA on 6 December 2007. Under its terms (Chapter 24), the federal government is similarly obliged to adopt settlement legislation, introduced as Bill C-34, in order to complete the ratification process and give effect to the TFA.

Disputes over the boundaries of traditional territories affect numerous ongoing comprehensive claims in British Columbia and elsewhere, including that of the TFN.(39) In late November 2007, a judge of the British Columbia Supreme Court dismissed the petitions of four First Nations groups with overlapping claims – including three Douglas Treaties groups – that sought to prevent the signing of the TFA based on insufficient prior consultation and accommodation of their interests by the provincial Crown. The judge agreed with government lawyers that it would be impossible to finalize any treaties if every overlapping claim had to be resolved beforehand, and concluded that the petitioners’ claims would not be irretrievably harmed by the signing, “particularly having regard to the non-derogation clauses contained in the [TFA].”(40)

The TFA consists of 25 chapters that comprehensively define TFN rights, responsibilities and applicable processes in relation to Tsawwassen Lands, land and environmental management, forest resources, wildlife harvesting and fisheries allocations, taxation, dispute resolution and numerous other matters. In addition to the constitutionally protected treaty, the parties have concluded “side agreements” outside the treaty. They include an implementation plan and fisheries guidelines as well as agreements related to fiscal financing, real property tax coordination, tax treatment and own-source revenue.

Although it is beyond the scope of this paper to provide a detailed summary of the TFA’s contents, the following sections outline some significant features related to its General Provisions, Lands, and Governance chapters.

This pivotal chapter includes stipulations that:

The TFA’s alternative to explicit extinguishment provisions of prior land claim settlements returns to the “modified rights” approach originally set out in the 1998 Nisga’a Final Agreement. Under this “certainty” option:

Under the TFA, treaty settlement lands comprising 724 hectares include

Source: Government of British Columbia, Ministry of Aboriginal Relations and Reconciliation, “Fact Sheet: Tsawwassen Lands” (PDF, 4 pages).

All the provincial Crown lands to be transferred to the TFN under the TFA are currently within the Agricultural Land Reserve (ALR) governed by the BC Agricultural Land Commission Act. When the TFA takes effect, 207 hectares of Tsawwassen Lands will lose the ALR designation,(44) while the remaining Tsawwassen Lands and Other Tsawwassen Lands are to retain that designation. The 290 hectares of former reserve lands, being federal land, are currently and will remain excluded from the ALR (s. 31-34).

The Lands chapter also:

The TFN’s governance provisions:

Additional TG law-making authority is set out in various chapters of the TFA, each of which prescribes the scope of that authority, and, with one exception, specifies which of TG or federal/provincial laws is to prevail in case of conflict.(48) The exception is the Taxation chapter authorizing laws for the direct taxation of TFN members on Tsawwassen Lands, which provides that any such laws do not limit federal and provincial taxation powers (Chapter 20, s. 2).(49)

The TFA also contains provisions relating to the transition from the Indian Act’s application to TFN in certain areas (Chapter 3); to relationships between TFN and regional government (Chapter 17); and to a dispute-resolution mechanism to apply to conflicts among the Parties over the TFA’s interpretation, application or implementation, or a breach of the TFA (Chapter 22).

Financial components of the TFA are set out, in part, in the Capital Transfer chapter (Chapter 18)(50) and the Fiscal Relations chapter (Chapter 19). The latter provides for the negotiation and contents of five-year Fiscal Financing Agreements providing, inter alia, for funding of agreed-upon programs and services for TFN, including TFN contributions from its “own source revenue” [s. 2].(51) The most frequently reported estimate places overall costs associated with the TFA at around $120 million.

Bill C-34 consists of a preamble and 33 clauses, 12 of which are transitional, consequential amending or conditional provisions. It is generally typical of comprehensive claim settlement legislation. The following review gives a general overview of selected significant features of the bill and does not discuss every clause in the legislation. References in square parentheses are to provisions of the TFA.

Bill C-34’s substantive clauses are preceded by a six-paragraph preamble that will enter the annual statute book as an integral part of the legislation. A preamble is an interpretive measure employed to establish a context and rationale for legislation and may also underscore parliamentary intent in enacting it. In this case the preamble refers, inter alia, to the importance of reconciliation through negotiation and to negotiation of the TFA as a means of achieving a new relationship among the parties, and notes that its ratification is dependent on the enactment of federal legislation.

The bill confirms the TFA’s status as a treaty within the meaning of sections 25(52) and 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 (clause 3). It also approves the TFA, gives it effect, declares it to be valid and acknowledges it to have the force of law (clause 4). The provision mirrors its equivalent in the November 2007 BC settlement statute on whose adoption the Agreement’s validity also depends [Chapter 24, s. 11].(53)

Bill C-34 further stipulates, for greater certainty:

As has been the case in all previous legislation for the ratification of land claim settlements, Bill C-34 contains provisions for dealing with both potential inconsistency between itself (when enacted) or other federal laws and the TFA, and conflict between itself and other legislation. In accordance with the TFA’s terms [Chapter 2, s. 26-28], the bill makes it clear that (1) the constitutionally protected TFA will prevail over any inconsistent federal laws, including the settlement legislation (clause 5(1)), and (2) the latter is to prevail over conflicting federal laws (clause 5(2)).

Bill C-34 provides for payment of Canada’s financial obligations under the TFA out of the Consolidated Revenue Fund. The specific obligations referred to in clause 6 are those set out in: Chapter 4 (Lands), which requires Canada to provide TFN $440,000 to establish a Reconciliation Fund for legacy projects [s. 30], and slightly over $1 million to enable it to establish an Economic Development Capital Fund [s. 107]; and Chapter 18 (Capital Transfer and Negotiation Loan Repayment) providing for scheduled capital transfer payments to TFN totalling about $14 million, over $12 million of which consist of ten annual transfers commencing when the TFA takes effect [Schedule 1, clause 1].(55)

The legislation reiterates provisions of Chapter 4 of the TFA providing that as of the effective date, TFN owns the estate in fee simple of Tsawwassen Lands and Other Tsawwassen Lands.

Chapter 20 of the TFA calls for the parties to enter into a Tax Treatment Agreement (TTA) for the treatment of various tax matters, and federal and provincial legislation to give effect to it [s. 22-23]. The TTA has been concluded,(56) and Bill C-34 satisfies the requirement that it be given effect legislatively. The bill also gives the TTA force of law for the period that it is in effect, a minimum of 17 years [TTA, s. 13], and stipulates that the TTA is not part of the TFA and is not protected by sections 25 and 35 [Chapter 2, s. 58].(57)

Under section 7 of the Fisheries Act, the discretionary authority of the minister of Fisheries and Oceans to issue fishing leases or licences is restricted to those not exceeding nine years; leases/licences for any longer period must be authorized by the Governor in Council.Bill C-34 provides for ministerial authority, notwithstanding section 7, to conclude and implement the TFN Harvest Agreement that is called for in Chapter 9 of the TFA [s. 102], and whose term is 25 years, with the possibility of further extensions at the option of the TFN [Harvest Agreement, s. 3-4]. The TFA does not expressly require that settlement legislation give effect to this non-treaty side agreement.

As indicated above, the TFA provides for transitional exceptions to the general rule that, except for the purpose of determining “Indian” status, the Indian Act will have no application to TFN, Tsawwassen Members, Government and Institutions [Chapter 2, s. 39].(58) Bill C-34 reiterates these exceptions, clarifying that the cessation of application of that Act coincides with the coming into effect of the TFA (clause 12). The bill further provides – again in accordance with the TFA [Chapter 2, s. 40] – that as of that date the First Nations Framework Agreement on Land Management to which the TFN became signatory in 2003, the First Nations Land Management Act (FNLMA) and the TFN Land Code mandated by that Act will cease to apply to TFN, its members, Lands, Government and Institutions (clause 13(1)).(59) Notwithstanding the foregoing, any existing TFN by-laws, including implicitly those under the Indian Act or the FNLMA, such as the TFN Land Code, remain in effect on the former TFN reserve for 30 days following the TFA’s effective date (clause 13(2)).(60)

Under subsection 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867, Parliament has exclusive jurisdiction over “Indians and Lands reserved for the Indians.” Clause 15 satisfies a TFA requirement [Chapter 2, s. 20] that federal settlement legislation include a section providing for the application of British Columbia laws that would not apply of their own force owing to subsection 91(24) to TFN, its members, Government and Institutions, subject to Bill C-34 and any other federal laws (clause 15). The Nisga’a ratification legislation contains an equivalent measure.

Bill C-34 provides for judicial notice of the TFA, the TTA and TFN laws (clauses 16-17), signifying that evidence of their existence and contents need not be presented in court in the event of litigation. The bill further requires that the Attorneys General of Canada and British Columbia and the TFN be notified in advance of any legal proceeding in which the interpretation or validity of the TFA, or the validity or applicability of federal or provincial ratification legislation or any Tsawwassen Law, is at issue (clause 20).

The Governor in Council is authorized to make “any orders and regulations that are necessary” in order to implement the TFA or the TTA (clause 18). A similar general power has been conferred by legislation ratifying prior land claim accords. The bill does not specify what person or body would determine when or what regulations are necessary.

Bill C-34 stipulates that, barring the issuance of a replacement interest under the TFA Lands chapter, an existing interest in former TFN reserve land that was granted under either the Indian Act or the FNLMA continues in effect under its terms. Canada’s rights and duties as grantor of that interest are transferred to TFN as of the coming into effect of the TFA (clauses 21-22), following which Canada is not liable for any TFN action or omission in the exercise of (1) TFN rights and obligations relating to existing interests in land or (2) powers or functions relating to such interests under Tsawwassen Laws (clause 23).

The legislation also reiterates a TFA provision related to federal obligations under the FNLMA [Chapter 2, s. 41], stipulating that, as long as that Act remains in effect, Canada will indemnify TFN in respect of its former reserve lands as it would if the Act remained applicable to those lands (clause 24). This ongoing undertaking relates to section 34 of the FNLMA, which obliges the federal Crown to indemnify a First Nation covered by that Act for any loss incurred as a result of a Crown act or omission in relation to the First Nation’s land prior to the coming into force of its land code.

These Bill C-34 amendments to five federal statutes:

Bill C-34 will come into force on a date fixed by order of the Governor in Council, with the exception of two coordinating provisions at clauses 31 and 32,(61) and clause 19, under which the TFA’s eligibility and ratification chapters are deemed to have taken effect upon the signing of the TFA in December 2006.

Little response to Bill C-34 was noted. The TFA itself and the treaty process more generally were the subjects of mixed commentary since the closing stages of negotiation, largely by First Nations and non-First Nations observers within the province.

Non–First Nations observers raised the potential scope of the Tsawwassen Government’s direct taxation authority over non-TFN members as a significant source of concern. They viewed such authority as taxation without representation in light of the limited ability of “disenfranchised” non-members, the majority of residents on TFN lands, to participate in decision-making processes under the TFA. A second point related to taxation concerned the fact that the TFN will retain percentages of various tax revenues collected on TFN lands, a situation described as a more generous financing arrangement than is available to municipalities.

Critics also objected to the withdrawal of treaty settlement lands from the province’s agricultural land reserve. Concern about the loss of protected status for valuable farm land, a key issue in the region, was linked to uncertainty about its future use by TFN, in particular the extent of industrial development TFN’s eventual land use plan will entail, and the subsequent impacts of development.

Other criticisms suggested that costs associated with the TFA – and, by extrapolation, with province-wide treaties – have been underestimated, and that the TFA’s fisheries chapter and side agreement on fisheries promote a race-based fishery, providing TFN with special access to the commercial fishery. According to one view, overall the TFA and the modern treaty process and policy are divisive and promote segregation, and Bill C-34 ought to have been subjected to a free vote in Parliament.

On the other hand, some editorial comment, noting public acceptance of the need for treaties and the moral obligation to provide First Nations with economic opportunities, saw reason for optimism that the TFA and the Maa-nulth Final Agreements signal an important step forward, establishing that treaties are possible, and may offer a useful framework for other agreements. For other non-First Nations observers, since a primary objective of modern treaties is enhancement of economic development prospects for First Nations signatories, it would be unjust to restrict TFN’s land use planning, particularly in light of the scale of existing industrial development by non-First Nations interests on TFN traditional territory. They pointed out that treaty settlements inevitably involve trade-offs and costs such as the loss of ALR lands, which are balanced by TFN concessions in other areas.

Others, agreeing with the need for compromise by all, noted that even with the land and financial components of the TFA, TFN members face challenges in “catching up” that they are prepared to take on. Other commentary observed further that TFN should be trusted to develop its community plan, since TFN members are unlikely to endorse a plan to turn their relatively modest parcel of land into an industrial park.

The responses of BC First Nations spokespersons to the conclusion of the TFA and its ratification were also mixed. Members of the First Nations Summit, representing communities in the treaty process, characterized ratification of the TFA by TFN as a huge development and a step forward for the treaty process, despite ongoing challenges for communities throughout the province. Both Summit and AFN–BC leaders, while celebrating BC ratification legislation, cautioned government that continued progress cannot be assumed and that much remains to be done. A First Nations Summit News Release congratulating the TFN on completion of the TFA warned that “reaching further settlement agreements is in serious jeopardy unless the federal and provincial governments change their negotiating mandates and commit to act with integrity and in good faith in further negotiations, to ensure the recognition of aboriginal title and rights.”(62)

Individual community representatives noted that conclusion of the TFA and Vancouver Island Maa-nulth treaties addressed the concerns of many by establishing that there is an end-point to the negotiation process that a majority can accept. Furthermore, the fact that the treaties reflect the different circumstances and histories of the groups involved demonstrated government’s willingness to adapt the terms of treaties to individual communities, a fact reassuring to First Nations people.

The head of the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs, representing groups opposed to the treaty process, suggested the TFA would not kick-start that flawed system. In his view, First Nations communities opposing the process now outnumber those that support it. And, although respecting the TFN’s decision to proceed with its treaty, he called on the federal and provincial governments not to sign the TFA pending consultation with Douglas Treaties groups claiming overlapping rights. Concern about resolving overlaps prior to reaching final agreements was shared by the First Nations Summit.

[W]e have never [bought out] any Indian claims to lands nor do they expect we should – but we reserve for their aid and benefit from time to time tracts of sufficient extent to fulfil all their reasonable requirements for cultivation or grazing. If you now commence to buy out Indian title to the lands of British Columbia – you would go back [on] all that has been done here for 30 years past. … Our Indians are sufficiently satisfied … .Madill (1981), Ch. 1, “The Vancouver Island Treaties – The Significance of the Vancouver Island Treaties.”

The guarantee in this Charter of certain rights and freedoms shall not be construed so as to abrogate or derogate from any aboriginal, treaty or other rights or freedoms that pertain to the aboriginal peoples of Canada. …The section has often been referred to as a “shield” for the safeguard of collective Aboriginal and treaty rights.

Source: Government of British Columbia, Ministry of Aboriginal Relations and Reconciliation, “Appendices to Tsawwassen First Nation Final Agreement, AppendixA” (PDF, 372 pages).

© Library of Parliament