Any substantive changes in this Legislative Summary that have been made since the preceding issue are indicated in bold print.

Bill C-93, An Act to provide no-cost, expedited record suspensions for simple possession of cannabis, was introduced in the House of Commons by the Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness on 1 March 2019 and received first reading that same day.1 On 6 May 2019, the bill was referred to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Safety and National Security (the committee), which reported the bill with amendments on 28 May 2019. The House of Commons concurred in the report, with amendments, and the bill was read a third time and passed by that chamber on 6 June 2019. The Senate, which made no amendments, passed the bill on 19 June 2019. Bill C-93 received Royal Assent on 21 June 2019.

The introduction of this bill follows the passage of the Cannabis Act,2 most of whose provisions came into force on 17 October 2018. That Act legalized several cannabis related activities, such as the possession of 30 g or less of dried cannabis or equivalent in a public place, and the possession of four or fewer cannabis plants per dwelling house. The result is that there are individuals with criminal records for past activities that are no longer considered criminal offences.

Bill C-93 amends the Criminal Records Act (CRA)3 to allow individuals who were convicted for possession of cannabis products before 17 October 2018 to request a record suspension (formerly known as a pardon) without having to wait the usual period of time and without being required to pay a fee.4 The Minister of Justice published a “Charter Statement” declaring that he has examined the bill and has not identified any potential effects on the rights and freedoms protected by the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (Charter).5

Individuals who were convicted in Canada or convicted abroad and transferred to Canada under the International Transfer of Offenders Act may request a record suspension from the Parole Board of Canada (Parole Board) after completing their sentence.6 A sentence is considered completed, for the purpose of applying for a record suspension, when

Because of the 2018 Supreme Court of Canada decision in R. v. Boudreault, outstanding victim surcharges imposed on or after 24 October 2013 are not considered in assessing when the waiting period begins because they were found to be unconstitutional.8

Individuals who receive an absolute or conditional discharge do not need to apply for a record suspension, as no conviction has been registered against them. If a discharge is received after 24 July 1992, it is automatically removed from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) systems one year after the court decision. For discharges prior to that date, a request for the information to be removed must be made to the RCMP.9 Similarly, young persons do not need to apply for a record suspension, as their records are destroyed or archived based on time periods set out in the Young Offenders Act or the Youth Criminal Justice Act, unless the persons are also convicted as adults.10

There are a few situations where a record suspension can be revoked or cease to have effect.11 For example, if an offender is convicted of a new offence, the record that was suspended may be reactivated in the RCMP’s Canadian Police Information Centre (CPIC). As outlined in the next section of this Legislative Summary, in addition, some offenders are ineligible for a record suspension.

Amendments to the CRA passed in 2010 and 2012 made several changes to record suspensions, including these:

The fees for a record suspension were increased from $50 to $150 in 2010 and then to $631 in 2012, which was the full cost-recovery amount at that time.13 The fee has since increased to $644.88.14

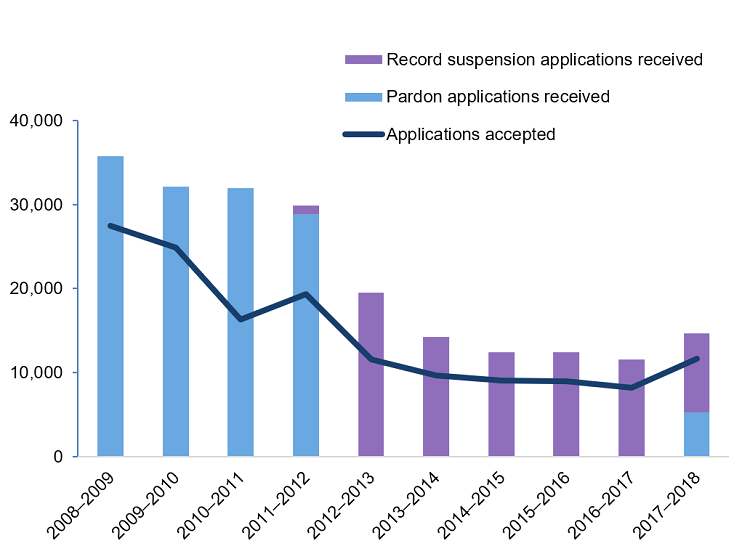

As shown in Figure 1, the volume of applications for record suspensions decreased significantly after the changes in 2010 and 2012. In the period 2002–2012, the Parole Board received about 25,000 applications per year, of which about 20,000 were accepted for processing (80%). In 2017–2018, it received 14,661 applications, of which 11,596 were accepted (79%).15

Figure 1 – Number of Pardon and Record Suspension Applications Received and Accepted, 2008‑2018

Source: Figure prepared by Library of Parliament using data obtained from Parole Board of Canada, “Figure 42: Pardon and Record Suspension Applications,” Performance Monitoring Report 2017–2018 ![]() (3.38 MB, 150 pages), p. 60.

(3.38 MB, 150 pages), p. 60.

Constitutional challenges to the retroactive application of the changes were successful in British Columbia and Ontario.16 For a period of time, applicants for a record suspension who committed an offence prior to the amendments in 2010 and 2012 in those two provinces were assessed based on the pardon criteria in force on the day that they committed the offence.17 Based on a 19 March 2020 decision of the Federal Court, that is now the case throughout the country.18

The CRA does not define the term “criminal record.” Rather, it uses the term “judicial record of the conviction” rather than “criminal record” to describe the record of a person’s conviction. The Act requires that, if a record suspension is granted, the judicial record of the conviction be kept separate and apart from other criminal records.19 However, because the CRA is federal legislation, it applies only to records held by federal organizations and is not binding on municipal or provincial police.

Records of convictions are not entirely centralized in Canada. They may be held in the national repository of the RCMP, but they can also be held by provinces and territories or at a local courthouse.20 The latter possibility is particularly the case for summary conviction offences, for which fingerprints are not always taken. Fingerprints are required for a record to be included in CPIC.21 For this reason, applicants for a record suspension must request their records from the RCMP, any court where they were convicted, and local police in every city or town they have lived in for three months or more during the past five years. Applicants must pay any associated fees prior to making their application.22

A record suspension does not erase a criminal record, but it does keep the record separate and apart from other criminal records so that it will no longer show up in a search of CPIC. The Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness must provide approval for any federal agency to give out information about the conviction once a record suspension has been granted.23 While record suspensions apply only to records kept by federal organizations, most provincial and municipal criminal justice agencies also restrict access to their records where a record suspension has been granted.24

A record suspension can have an impact in many areas of life. It can assist an offender in seeking employment and educational opportunities, and to secure housing.25 In addition, certain disqualifications relating to a conviction, such as a bar on federal government contracting or eligibility for Canadian citizenship, are no longer applicable following a record suspension.26 It is also illegal under the Canadian Human Rights Act (CHRA) to discriminate, in areas of federal jurisdiction, against someone because of a conviction for an offence for which a “pardon” has been granted.27 Human rights law varies significantly between provinces and territories. While some jurisdictions provide the same protection as the CHRA against discrimination based on a criminal record for which a record suspension or pardon has been granted, others provide only partial or no protection from such discrimination.

A record suspension does not guarantee entry or visa privileges in another country.28 Record suspensions can also assist in addressing inequities within the justice system that affect certain groups. The government news release published when Bill C-93 was introduced states: “The enforcement of cannabis laws in the past disproportionately affected certain Canadians, particularly members of Black and Indigenous communities.”29 While there is no comprehensive race-based data in Canada regarding this issue, this statement appears to be supported by the available data. For example, in April 2018, Vice News published information it received through access to information requests from six police services regarding single charge cannabis possession arrests by race, among other factors. The period covered was 2015 to 2017. The news service had the data analyzed by two experts at the University of Toronto, Akwasi Owusu-Bempah and Alex Luscombe, who found, for example, that Indigenous people in Regina were nine times more likely to be arrested for cannabis possession than whites in that city. Black people in Halifax were five times as likely as whites to be arrested for this reason. Mr. Owusu-Bempah stated, based on this and other research:

We know that rates of cannabis use are relatively similar across racial groups. So the fact that specific groups have been disproportionately targeted for drug law enforcement, especially black and Indigenous populations, strengthens that need for amnesty and for pardons. … Because those groups have not only been disproportionately targeted, they have been disproportionately harmed by the consequences of having a criminal record.30

Bill C-415, An Act to establish a procedure for expunging certain cannabis-related convictions, was introduced in the House of Commons by then Member of Parliament Murray Rankin and received first reading on 4 October 2018, but was defeated at second reading.31 The primary difference between Bill C-415 and Bill C-93 is that Bill C-415 sought to expunge records, as opposed to suspending them. Expungement results in the permanent destruction of records of the conviction from federal databases. The person is deemed never to have been convicted of the offence.32 The government backgrounder for Bill C-93 explains that expungement is an “extraordinary measure” for cases where the law should never have existed, such as where it violates the Charter.33

Bill S-258, An Act to amend the Criminal Records Act and to make consequential amendments to other Acts, was introduced in the Senate on 20 February 2019 by Senator Kim Pate, but it died on the Order Paper when the 2019 federal election was called.34 That bill proposed to replace the term “record suspension” with “record expiry” and to make a record expiry automatic after two or five years, depending on the type of offence and the sentence. The Parole Board would continue to evaluate applications in certain circumstances, such as requests for “advance record expiry,” which would be permitted if specific conditions were met. This bill would have applied much more broadly than Bill C-93 and would not have been limited to cannabis possession.

The government backgrounder for Bill C-93 explains that the decision was made not to make a record suspension for cannabis possession automatic in the bill so that applicants will be required to satisfy the Parole Board that they have been convicted of simple possession of cannabis only, and so help to ensure that complete and up to date information is before the Parole Board when the file is processed.35 On this point, Catherine Latimer of the John Howard Society cautioned the committee, during its 2018 study on record suspensions, that “[i]f it’s not automatic, you’re penalizing people with cognitive impairments, people who are marginalized, people who are poor, or people who are illiterate” because of the complexity of the application process.36

As noted above, the committee recently studied a motion regarding record suspensions. The committee considered Motion 161 at two meetings in November and December 2018 and reported back to the House of Commons on 11 December 2018. The committee made several recommendations, including that the government review record suspension fees, the complexity of the process and the use of the term “record suspension.” The report also called for the government to “examine a mechanism to make record suspensions automatic in specific and appropriate circumstances.”37

On 14 November 2017, the Chair of the House of Commons Standing Committee on Health wrote a letter, adopted by the majority of that committee, to the ministers of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness, Justice, and Health, which outlined several issues raised by witnesses during hearings regarding Bill C-45, whose provisions relate to the creation of the Cannabis Act. In its letter, that committee urged the government to improve the record suspension system for cannabis-related convictions, with particular attention to barriers faced by marginalized individuals.38 The Standing Senate Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs’ report to the Senate regarding its study of parts of Bill C-45 also mentioned that witnesses had noted that the bill did not provide a specific mechanism for record suspensions for past convictions for cannabis-related offences, and it stated that the Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness was considering how to address the issue.39

Bill C-93 contains nine clauses amending the CRA. Key clauses are discussed in the following section. In addition to the main changes outlined below, the bill amends other provisions of the CRA to reflect the main changes.

Section 4(1)(a) of the CRA states that before requesting a record suspension, a person must wait 10 years following a conviction for an indictable offence or following a conviction in the military justice system for a service offence with one of the punishments listed in that provision.40 According to section 4(1)(b), the waiting period is five years upon summary conviction or if the conviction is for a service offence not referred to in section 4(1)(a).

Clause 4(2) of Bill C-93 amends section 4 of the CRA to permit persons convicted only of offences outlined in Schedule 3 of the bill (cannabis possession offences) to apply for a record suspension immediately after having completed their sentences. According to the first reading version of the bill, new section 4(3.2) of the CRA provided that, to be eligible, all fines must be paid as well. However, in committee, that section was amended for Schedule 3 offences. For such offences, fines and victim surcharges do not need to be paid to be eligible for a record suspension. The committee also added a new section 4(3.11), which states that when someone is convicted of both a Schedule 3 offence and other offences, the calculation of the waiting period before being able to apply for a record suspension does not take into account the sentence for the Schedule 3 offence. New section 4(3.2) clarifies that in cases where an applicant has been convicted for multiple offences, if a fine or victim surcharge was imposed for both the Schedule 3 offence and other offences, it must be paid before the person is eligible to apply for a record suspension (new section 4(3.21)). New section 4(3.3) also waives the fee that is charged to apply for a record suspension for a Schedule 3 offence. Other fees for criminal record checks and court documentation remain.

As set out in clause 4(2) of the bill, new section 4 of the CRA states that only individuals who have been convicted of an offence referred to in the new Schedule 3 to the Act may apply for a record suspension before the applicable waiting period and without paying the application fee. Schedule 3 lists three categories of offences, all of which relate to cannabis possession:

Before the CDSA was amended following the adoption of Bill C-45 on 17 October 2018, Schedule II included Item 1, which listed cannabis, as well as its preparations and derivatives, and sections 4(4) and 4(5) outlined the punishments for possession of substances listed in Schedule II. With the adoption of Bill C-45, Item 1 of Schedule II was repealed, and under the Bill C-93 amendments to section 4, the usual waiting period and fees do not apply for applications for record suspensions connected with offences under those pre–Cannabis Act provisions.

A number of other possession offences relating to cannabis, such as possessing the equivalent of more than 30 g of dried cannabis in a public space and possessing more than four cannabis plants, do remain illegal under the new Cannabis Act. If a person is convicted for simple possession of cannabis under that Act, that conviction is not covered by the amendments to the CRA and the normal waiting period and fees apply.

In addition, synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists, which are listed in Item 2 of Schedule II to the CDSA, remain illegal. Wait times and fees will continue to apply for offenders convicted of offences relating to drugs listed in Item 2 who wish to apply for a record suspension.

The NCA, which was in force prior to the CDSA, did not distinguish between synthetic and natural cannabis and included both under Item 3 of the schedule to that Act. Because all but one of the substances listed both in former Item 3 of the schedule to the NCA and in former Item 1 of Schedule II to the CDSA are the same, possession offences for substances listed under former Item 3 of the NCA schedule, like those for the former Item 1 substances under Schedule II of the CDSA, are not subject to the waiting period or the fee. The exception is pyrahexyl, which was listed under Item 3 of the schedule to the NCA but appears under current Item 2 of Schedule II of the CDSA (as “parahexyl,” its alternative name). Since, as mentioned above, drugs listed in Item 2 remain illegal, it appears that under the first reading version of Bill C-93, a record suspension would have been possible for no fee and without a waiting period for an offence relating to pyrahexyl if the conviction was under the NCA, but not under the CDSA.43 The schedule to Bill C-93 was amended in committee to clarify that synthetic forms of cannabis that remain illegal and are not identical to plant-based cannabis do not benefit from the measures introduced by the bill.

As set out in clause 4(3) of Bill C-93, new section 4(5) of the CRA allows the Governor in Council to amend Schedule 3, meaning that Cabinet can change the list of offences for which a record suspension may be granted without a post-sentence waiting period or a record suspension fee.

While decisions on record suspension applications must usually be made by one or more Parole Board members, clause 2 of Bill C-93 provides that applications for a record suspension for possession of cannabis are dealt with by employees of the Parole Board.

Section 4.1(1) of the CRA requires that the Parole Board be satisfied that the applicant has been of good conduct during the five- or 10-year waiting period and has not been convicted of an offence under an Act of Parliament during that time. Where the waiting period is 10 years, it must also be satisfied that the record suspension “would provide a measurable benefit to the applicant, would sustain his or her rehabilitation in society as a law-abiding citizen and would not bring the administration of justice into disrepute.”

Bill C-93 adds new section 4.1(1.1) to the CRA to require the Parole Board to provide the record suspension if the applicant has been convicted only of an offence in Schedule 3 of the bill (i.e., cannabis possession) and has not been convicted of a new federal offence. The evaluation that is required under section 4.1(1) is neither required nor permitted in these cases.

A new section 4(4.11) was introduced in committee and then modified in the House of Commons. The new section states that for applications for a record suspension for possession of cannabis, the Parole Board may not require a certified copy of information contained in court records unless the police records or Canadian Armed Forces records do not provide sufficient information to establish whether the applicant was only convicted of a Schedule 3 offence and only sentenced to a fine, victim surcharge or both.44 In addition, the committee added a new section 4.1(1.2) stating that a record suspension for cannabis possession cannot be revoked under section 7(b) of the CRA.

Section 4.2(1)(a) of the CRA requires that the Parole Board ensure that inquiries are made to determine whether the applicant is eligible for a record suspension. Under section 4.2(1)(b), the Parole Board must also ensure that inquiries are made to ascertain the applicant’s conduct since conviction, and where the offence was prosecuted by indictment,45 the Parole Board, under section 4.2(1)(c), may have inquiries made regarding any factors it may consider in determining whether a record suspension would bring the administration of justice into disrepute. Clause 6 of the bill bars the inquiries described in sections 4.2(1)(b) and 4.2(1)(c) in the case of applications for a record suspension for cannabis possession. In committee, amendments were introduced so that any inquiries under section 4.2(1)(a) are not to take into account the non-payment of a fine or victim surcharge for Schedule 3 offences. Where multiple offences, including a Schedule 3 offence, are involved, the inquiries under sections 4.2(1)(b) and 4.2(1)(c) are not to take account of any Schedule 3 offence.

Section 6(2) of the CRA provides that once a record is suspended, any records in the custody of the Commissioner of the RCMP or of any department or agency of the federal government must be kept separate and apart from other criminal records. Such records and their existence may only be disclosed with the approval of the Minister. In committee, the bill was amended so that ministerial approval is no longer required when a suspended record is disclosed for the purposes of sections 734.5 and 734.6 of the Criminal Code and section 145.1 of the National Defence Act for the non-payment of a fine or victim surcharge imposed for a Schedule 3 offence.46

If an application is made before Bill C-93 comes into force but the application has not yet been “dealt with and disposed of,” according to clause 8(2) of the bill, the application is to be dealt with in accordance with the provisions of the bill. However, in such a case, the $644.88 application fee may be required where inquiries have already been made into whether the applicant is eligible for a record suspension.

The CRA requires applicants to wait for one year to reapply for a record suspension if their application is refused. Clause 8(3) of the bill clarifies that this provision does not apply to applicants with a conviction for cannabis possession if the refusal took place within one year before the day on which Bill C-93 comes into force.

In committee, a requirement was added regarding the annual report under section 11 of the CRA in the year after Bill C-93 comes into force. The amendment requires the report to include information on the number of applications dealt with and disposed of, the associated costs and the number of record suspensions ordered and refused.

The Act will come into force on a day to be fixed by order of the Governor in Council.

* Notice: For clarity of exposition, the legislative proposals set out in the bill described in this Legislative Summary are stated as if they had already been adopted or were in force. It is important to note, however, that bills may be amended during their consideration by the House of Commons and Senate, and have no force or effect unless and until they are passed by both houses of Parliament, receive Royal Assent, and come into force. [ Return to text ]

a fine of more than five thousand dollars, detention for more than six months, dismissal from Her Majesty’s service, imprisonment for more than six months or a punishment that is greater than imprisonment for less than two years in the scale of punishments set out in subsection 139(1) of the National Defence Act.[ Return to text ]

© Library of Parliament