The decline in youth voter turnout in Canadian federal elections was first observed following the 1984 federal general election. Since then, youth voter turnout remains lower than the turnout for all other age groups, despite intermittent increases in recent years.

Research on voter participation suggests that the trend toward higher voter turnout as populations age seems to be weakening. This phenomenon could have serious consequences in the context of generational replacement, though some authors argue that the life-cycle effect occurs later in life among present generations.

There are many possible reasons for youth voter disengagement. Socio-demographic factors, education and being born in Canada have an important impact on whether youth vote. Studies have also found that interest in politics, or rather, a lack thereof, and knowledge of politics influence youth engagement, as many young people do not see themselves represented in party platforms. They also express a lack of trust in the system, both in the utility of voting and in the Office of the Chief Electoral Officer of Canada, commonly known as Elections Canada, itself. However, media use reportedly has a positive impact overall on the acquisition of political knowledge. Reading newspapers and consulting news websites exert a strong positive influence on the electoral participation of young Canadians, although watching television and listening to the radio do not have as pronounced an effect.

In response, there have been various initiatives to increase the electoral participation of youth in Canada. Elections Canada has studied the issue and has worked on facilitating access and registration on the voters’ list. It has used advances in technology to facilitate online registration, lead communication and awareness campaigns, and interact with the general public through social media. Parliamentary and electoral simulation exercises give young people their first exposure to the political process and introduce them to the basic aspects of parliamentary debate. Accordingly, Elections Canada has supported programs that hold parallel elections in schools and has updated its education material on civic engagement.

This HillStudy examines trends in youth voter turnout for federal elections in Canada from 1965 to 2021 and considers the effects of declining voter participation on Canadian democracy. It explores determinants of Canadian youth voter participation as examined through various surveys and studies. Finally, it highlights initiatives to encourage youth engagement in federal elections.

From 1980 to 2021, Canada’s youngest voters turned out for federal general elections in numbers well below the turnout rate for all other demographic groups. Although youth voter turnout was significantly higher for the 42nd general election in 2015 than in previous years, it was still below the overall voter participation rate, and it decreased again in 2019. This disengagement from participation in the electoral process by Canadian young people has acted as a significant downward drag on overall turnout figures.1

Average overall voter turnout2 in federal general elections has remained below 70% since 1993.3 The 2008 election had the lowest voter turnout since Confederation, with an estimated 56.5% of eligible voters casting ballots.4 While overall turnout rose to 67% in 2019,5 it fell to 62.5% in the 2021 election.6

According to a number of studies, the conventional wisdom that non-voters become voters as they get older may no longer hold true. That being said, the high turnout in the 2015 election warranted reconsidering the engagement of youth in the democratic life of Canada. However, that turnout was not sustained in 2019, again putting into question the engagement of the youngest cohorts of voters in Canada.

This paper provides a brief overview of youth voter turnout from 1965 to 2021 and goes on to consider the effects of declining voter participation on Canadian democracy. The determinants of Canadian youth voter participation are subsequently examined through the findings of various surveys and studies. Steps taken by the Office of the Chief Electoral Officer of Canada, commonly known as Elections Canada, to remedy the situation are then discussed.

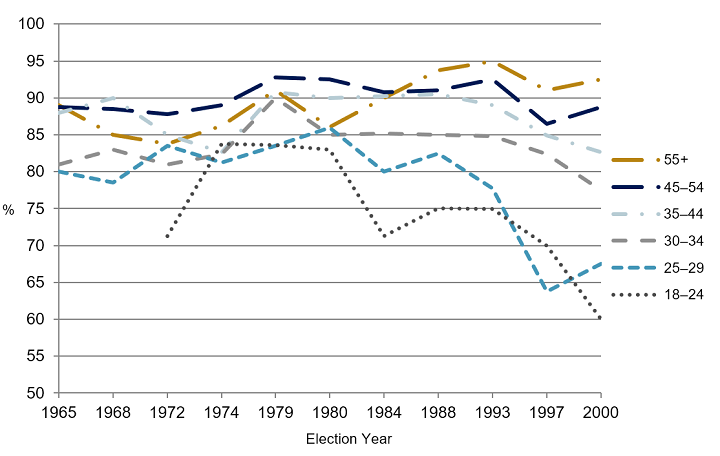

Using voter turnout data from the Canadian Election Study for the years 1965 to 2000, a number of observations can be made for the period from 1965 to 1980 (see Figure 1 below). First, the youngest age groups (18–24 and 25–29) were always among the cohorts with the lowest voter turnout. At times, the gap between the participation of the two youngest cohorts and the turnout of voters aged 35 and up rose to around 10%. This gap was relatively modest, however, compared to the disparity that would exist during the years following this period. Fluctuations between age cohorts were not particularly significant from 1965 to 1980, with the exception of an estimated 13% increase in voter turnout by the 18–24 cohort from the 1972 election to the 1974 election.

Figure 1 – Estimated Voter Turnout in Canada by Age Group, 1965–2000

Note: Canada has a secret ballot. To collect data on voter turnout, the Canadian Election Study therefore relied on post-election surveys. Methodologically, these surveys tended to produce higher turnout rates than official rates, in particular because of the social desirability of stating that one had indeed voted. The sample of survey respondents also tended to contain more voters than non voters. The data shown in the figure have not been adjusted to compensate for these methodological issues.

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from “Figure 1, Reported voter turnout in federal elections by age group, 1965–2000,” in Margaret Adsett, “Change in political era and demographic weight as explanations of youth ‘disenfranchisement’ in federal elections in Canada, 1965–2000,” Journal of Youth Studies, Vol. 6, No. 3, 2003, p. 251.

In the federal general elections held between 1984 and 2000, the reported voter turnout rates for the cohorts aged 18 to 24 and 25 to 29 declined sharply (as shown in Figure 1 above). Voter turnout for the 18–24 age group fell approximately 10 percentage points, from a rate of just over 70% to just over 60%, representing a decrease of 15%. The voter turnout rate for the 25–29 age group fell similarly during this period, though a slight recovery was noted from the 1997 federal general election to the 2000 election.

During the same period, increases and decreases in turnout among the older cohorts were more or less in line with those of the youngest cohorts. The fluctuations, however, were of lesser magnitude than those for the two youngest cohorts, and the decline in voter turnout for the four oldest age cohorts was relatively minor. Indeed, the voter turnout for the 55+ age group actually rose during this period and, in 1993, this cohort produced the highest rate of voter turnout recorded in the study.

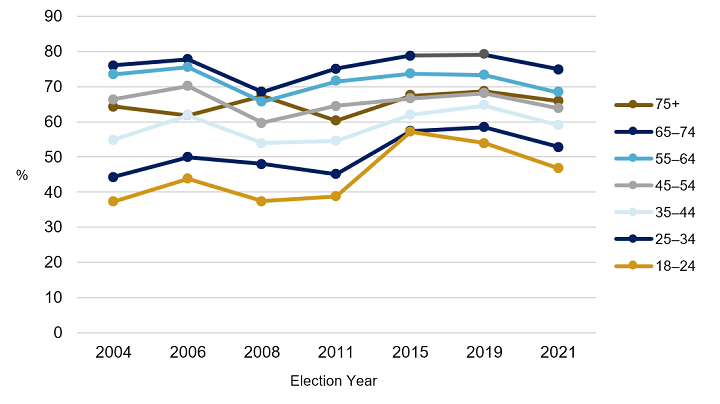

To calculate voter turnout from 2004 to 2011, Elections Canada employed a different method7 than that used in the Canadian Election Study. For this reason, the estimated percentages, by age cohort, of the Canadian population that voted in the federal general elections since 2004 are not comparable to the percentage estimates reported for previous elections in the Canadian Election Study. Nevertheless, trends and patterns in estimated voter turnout presented in the two data sets can still be compared.

Figure 2 – Estimated Voter Turnout in Canada by Age Group, 2004–2021

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from Elections Canada, “Estimated Voter Turnout by Age Group (2004–2015) (Based on electoral population),” Retrospective Report on the 42nd General Election of October 19, 2015 ![]() (939 KB, 93 pages), September 2016, p. 31; Elections Canada, Estimation of Voter Turnout by Age Group and Gender at the 2019 General Election; and Elections Canada, Turnout by age: Estimation of Voter Turnout by Age Group and Gender at the 2021 General Election.

(939 KB, 93 pages), September 2016, p. 31; Elections Canada, Estimation of Voter Turnout by Age Group and Gender at the 2019 General Election; and Elections Canada, Turnout by age: Estimation of Voter Turnout by Age Group and Gender at the 2021 General Election.

First, the gaps in voter turnout between the youngest and the second-youngest age cohorts persist in both sets of data. The gap between these two cohorts varies from about 6% to 11% (see Figure 2 above). A similar gap was reported by the Canadian Election Study for the federal general elections of 1984, 1988, 1993 and 2000.

Another gap – between the voter turnout rate of the two youngest age cohorts and the average voter turnout rate at each federal general election – can be found in both the Elections Canada voter turnout estimates and the Canadian Election Study estimates. Since 1984, the estimated voter turnout of the two youngest cohorts has been lower than that of all other age cohorts.8 In the 2004, 2006, 2008 and 2011 federal general elections, the gap between the estimated average overall voter turnout and the estimated turnout of the second-youngest age cohort was between 8.5% and 14%, while the same gap hovered between 19% and 21% for the youngest cohort. From 2004 to 2011, the youngest cohort’s estimated voter turnout rate fluctuated between 37% and 44%.

In the 2015 federal election, the overall voter turnout rate for the 18–24 age group increased to 57.1%, a rise of 18 percentage points from 2011 (see Figure 2 above). Turnout also went up among those aged 25 to 34, increasing from 45.1% in 2011 to 57.4% in 2015. While turnout rates increased for all age groups in 2015, the largest upswings were recorded by the 18–24 and 25–34 age groups.9

Although youth voter turnout rose in 2015, it did not continue doing so in 2019. The voter turnout rate for the 18–24 age group fell from 57.1% in 2015 to 53.9% in 2019. However, it did rise from 57.4% to 58.4% among those aged 25 to 34.

In the 2021 federal election, among eligible youth aged 18 to 24, only 46.7% cast a ballot, down from the 2019 figure. In this election, this figure also fell among youth aged 25 to 34 to 52.8%.

Regardless of rises and falls, youth voter participation consistently remained below the national average of 66.1% in 2015, 67% in 2019 and 62.2% in 2021.10

Research on voter participation suggests that the trend toward higher voter turnout as populations age (the so-called “life-cycle effect”) seems to be weakening. This phenomenon could have serious consequences in the context of generational replacement. On the other hand, some authors argue that the life-cycle effect remains observable among present generations, but that it occurs later in life.

The consensus view is that voter participation follows an age-related cycle. Owing to various structural, social, moral and economic factors, a smaller percentage of young people vote compared to older people.11 As young non-voters age, they are more likely to vote. This is known as the “life-cycle effect.”

A number of recent studies, however, indicate that this trend is no longer as verifiable as it was in the past. In a working paper published by Elections Canada in 2011, Youth Electoral Engagement in Canada, authors André Blais and Peter Loewen sought to determine what is and is not known about the extent and causes of youth electoral engagement (and non-engagement) in Canada. They demonstrated that the life-cycle effect is less pronounced among cohorts born in the 1970s or later than it is among previous generations of voters. In this connection, they noted:

There seems to be a persistent downward trend in the turnout rate of new cohorts. The consequence of this is that despite the fact that young voters are more likely to vote as they get older, they are beginning at such a low level of participation that overall turnout can only be expected to decline.12

This pattern is likely to have far-reaching consequences as generational replacement proceeds over time. However, Blais and Loewen indicate that there may simply be a delay in the life-cycle effect, as “the process of ‘maturation’ takes more time than before”13 among young people today.

Constance Flanagan and Peter Levine agree with this assessment, speculating that the trend manifests itself in a delayed transition to adulthood and a consequent much later civic engagement than was the case for previous generations.14 Other authors have argued that political disengagement may be only temporary for some of today’s young non-voters and that this generation should not be viewed as a monolithic whole.15 These researchers contend that it would be a mistake to view all of these non voters as permanently cynical or uninterested, and they argue that non participation may be a result of such temporary factors as the need to combine work with post-secondary education, leaving less time for engagement.16

In studies that grouped the electorate into approximate “generations” according to age and tracked their voting propensities over time, researchers found that voters born before 1945 and between 1945 and 1959 who felt it was their duty to vote were being replaced by younger generations of voters (born after 1960) who were less likely to exercise their right to vote.17 Authors theorize that this phenomenon may explain the drop-off in voter participation observed since the 1993 general election, resulting in the ongoing decline in the overall voter turnout rate.18 In fact, if young people who are less likely to vote continue to replace cohorts that are more inclined to vote, average overall voter turnout could plummet as the age groups largely responsible for propping up overall voter turnout continue to disappear and are not replaced by generations with an equivalent level of engagement.

That being said, authors who have written about young people’s delayed participation in civic life or the temporary nature of their failure to vote tend to be more optimistic in their predictions concerning the future of democratic life in Canada. In their view, not voting at the age of 18 is not necessarily indicative of a long-term trend toward disengagement.19

While the overall turnout rate among young voters remains below the Canadian average of 66.1%, the gap is narrowing. The higher voter turnout rate for the 18–24 age group in the 2015 federal general election and the 25–34 age group in the 2019 federal general election hints at a possibility for change. Certainly, this uptick in youth voter turnout offers no guarantee for the future, but the many studies attesting to the habit-forming nature of the act of voting would seem to indicate that there may be room for hope.20

Blais and Loewen uncovered a number of socio-demographic factors that may affect the voting habits of young people. They found that today’s youth are less likely to be married, are better educated, are slightly less religious, earn less income and are more likely to have been born in Canada than young people of previous generations.

The authors argued that, of these socio-demographic factors, education and being born in Canada are the most influential in young people’s decision to vote. The data compiled by the authors suggest that students aged 18 to 24 are 9% more likely to vote than those in the same age group who are not studying, and that Canadian-born youth aged 18 to 24 are 12% more likely to vote than youth born outside Canada. Accordingly, the authors suggest that “those who are born outside of Canada take slightly longer than their Canadian-born counterparts to come to socialize into Canadian politics.”21

In a study prepared for Elections Canada in January 2015, Antoine Bilodeau and Luc Turgeon reached conclusions similar to those of Blais and Loewen concerning the impact of being born in Canada on youth voting propensity. With respect to the student status of voters, however, the authors determined that being a student reduced the propensity to vote in the 25–34 age group but had no noticeable effect on members of the 18–24 age group. While they were unable to explain this result, the authors hypothesized that “age trumps the student effect.”22

For Blais and Loewen, political factors – namely interest in and information about politics – have an even greater effect on youth voting behaviour than do socio-demographic factors.

It is often said that political party election platforms do not include issues that are important to young people. This suggestion was challenged, however, by political scientists who conducted a study on behalf of Elections Canada following the 2004 federal election. In fact, according to Elisabeth Gidengil and her co-authors,

[i]ssues that concern many young people are on the political agenda, and the political parties are taking positions on these issues. The problem seems to be that too often these messages are just not registering with a significant proportion of younger Canadians.23

Bilodeau and Turgeon do not address the matter of issues, but they contend that young people have less of a stake in politics, whether it is at the federal or provincial level. They also note that young people are less likely than members of older age groups to feel an attachment to a political party.24

For author Heather Bastedo, a young person’s failure to vote in an election does not mean that he or she is not interested in politics. She notes that young people who are more likely to exhibit political engagement, such as those with some university education, will be more interested in national and international political issues, while young people with fewer years of schooling will be more interested in local political concerns that are much closer to their own personal experience.25

The authors of the 2004 study prepared for Elections Canada asserted that there were “striking” gaps in young Canadians’ knowledge of politics.26 Indeed, the consensus view among political scientists is that a significant number of young voters go to the polls without the necessary tools to make an informed decision.27 The 2015 National Youth Survey revealed not only that youth were less knowledgeable than older adults when it came to politics, but also that they found it more difficult than their older counterparts to obtain information about political parties and candidates.28

For their part, Bilodeau and Turgeon found that younger Canadians are less likely than older Canadians to express political opinions, possibly indicating a lack of knowledge of Canadian political institutions.29 In a study conducted for the Institute for Research on Public Policy (IRPP), Henry Milner established a cause-and-effect relationship between the level of political knowledge and youth electoral participation.30

Apart from having limited knowledge about the political system, both young and old Canadians show a lack of interest in public affairs. Many of these people doubt that voting every four years can truly influence the decision-making process. As a result, people stay away from the polls, and this can lead to distrust and even cynicism over time.31

Bilodeau and Turgeon found that younger Canadians express less confidence in Elections Canada than do older Canadians, thereby reducing their propensity to vote. Young voters also seem to have a less developed sense of civic duty. In fact, the authors found that Canadians aged 18 to 24 are substantially less likely than older Canadians to feel guilty about not voting. Conversely, Bilodeau and Turgeon observed less of a gap between age groups when considering the perception that one’s vote could make a difference. While 77% of Canadians aged 35 years and older felt that this was true, the proportions were 64% and 63% respectively for the 18–24 and 25–34 age groups.32

When the issue of cynicism is raised, the media are often singled out as the culprits. Television is a particular target since it tends to focus on the conflicts in politics.33

Yet media use reportedly has a positive impact overall on the acquisition of political knowledge, although its effect depends on the medium used. Reading newspapers and consulting news websites exert a strong positive influence on the electoral participation of young Canadians, while watching television and listening to the radio do not have as pronounced an effect.

The voter turnout rate among young Canadians has been a source of concern for many years. A variety of measures have been proposed to address the decline in youth voter turnout, and those taken by Elections Canada in recent years are worth noting. Given the fact that not much time has elapsed since the most recent federal general election, relatively few studies have been published that examine the reasons for the significant increase in youth voter turnout over the rate recorded in the 2011 election. Hence, as of this writing, it is impossible to say whether the Elections Canada initiatives described in section 5.1 of this paper have had any direct impact on voter turnout.

The idea of lowering the voting age from 18 to 16 is raised regularly as a potential means of increasing the electoral participation of young Canadians. The Royal Commission on Electoral Reform and Party Financing recommended in 1991 that Parliament periodically revisit the issue.34 Advocates of lowering the voting age also point out that voting as a civic duty must be instilled in young people before they finish school (see section 5.1.4 of this paper). However, as yet, there is no solid evidence to suggest that such a measure would increase voter turnout rates in Canada, at least in the long term.35

Another proposal is to make voting mandatory. Careful consideration must be given before implementing this idea, however, because of the coercive nature of the measure and uncertainty about the state’s ability to enforce it. At any rate, according to Henry Milner, compulsory voting would produce a minimal increase in electoral participation.36

As an independent agency reporting to Parliament, Elections Canada administers the federal electoral system according to the framework set out in the Canada Elections Act.37 Apart from conducting and overseeing federal elections, the agency ensures that the electoral process is fair, transparent and accessible for all participants.

In 2004, the House of Commons unanimously adopted a motion calling on Elections Canada to undertake initiatives to encourage youth voter turnout in Canada.38

Addressing young voters’ lack of interest in the voting process has been a key issue for Elections Canada over the years. After each election, the agency conducts studies to determine the voter participation rate by age group and carries out surveys of all demographic groups. Elections Canada also created the “Inspire Democracy” website as a platform to disseminate research on youth participation and share information on how to enhance youth civic engagement in Canada.39

Elections Canada commissioned its first ever National Youth Survey (NYS) following the 2011 federal election, and it repeated the exercise after the 2015 and 2019 elections. The purpose of these studies was to provide a better understanding of the voting behaviour of youth aged 18 to 34 by gathering information on the access and motivational barriers to voting.40

Registering young voters remains a priority for Elections Canada. In each election, community relations officers are assigned to maximize youth access by conducting special registration campaigns in neighbourhoods with high concentrations of students and electoral districts where post-secondary institutions are located.

In the past, Elections Canada communicated with the heads of the main national student associations to discuss how best to facilitate voting by students on election day. For the January 2006 election, Elections Canada made sure that returning officers were especially attentive to young people, since the election period coincided with Christmas exams and holidays. Voter registration and polling stations were set up on campuses to make it easier for young people to vote. Along the same lines, as part of a pilot project in 2015, returning officers opened 71 satellite offices at select campuses, Friendship Centres and YMCAs to provide information, registration and voting services to youth.41

In 2007–2008, to facilitate access for all young Indigenous voters, Elections Canada worked with the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) to hold an Aboriginal youth forum.42 The agency also collaborated with the AFN for the 2006, 2008 and 2011 federal elections. Its primary mission in 2006 was to encourage First Nations people to exercise their right to vote; in 2008 and 2011, however, efforts focused primarily on getting information to First Nations electors in order to help them overcome barriers to voting.43 In 2015, Elections Canada signed a contract with the AFN in preparation for the federal election that same year; it exercised the option to renew its contract with the AFN for the 2019 general election. The contract contained three components: under the “research” component, the AFN would identify existing barriers to voting that electors from First Nations face; under the “communication” component, it would support Elections Canada’s communication efforts to ensure that electors from First Nations knew when, where and how to register and vote; and under the “outreach” component, the AFN would organize community awareness activities to convey key messages and identify priority federal electoral districts.44 These initiatives were directed at all age groups in all First Nations.

A number of recommendations in the AFN’s report, Facilitating First Nation Voter Participation for the 42nd General Election, were incorporated into Bill C‑76, An Act to amend the Canada Elections Act and other Acts and to make certain consequential amendments. More recommendations were made in Facilitating First Nations Voter Participation for the 43rd General Election, including

[c]omprehensive educational training or materials, developed in coordination with First Nations, for all Elections Canada election staff on First Nation participation in the federal electoral process, including information on historical barriers to First Nations participation, First Nation voter identification methods, and the recent effort to increase First Nations accessibility in the federal electoral process.45

Between 2011 and 2015, Elections Canada sent some 1.76 million letters to potential voters, asking them to register or to confirm their information.46 One month prior to the election of 21 October 2019, letters were sent to some 213,000 eligible electors aged 18 to 26.47

The Labour Force Survey conducted by Statistics Canada following the 2015 election revealed that, compared to the general population, a higher proportion of youth aged 18 to 24 viewed the requirement to produce a proof of identity as an obstacle to voting.48 This situation may be in part attributable to the 2014 amendments to the Canada Elections Act, which eliminated the voter information card as a piece of identification that could be used at polling stations.49 In the 2015 NYS, 12% of youth non-voters indicated that it would have been difficult for them to prove their identity.50

In addition to running ads in various media targeting youth (radio stations, digital screens on campuses and on buses, etc.),51 Elections Canada employed new communication technologies to reach out to youth voters as much as possible. In 2015, the online voter registration service, which was available for the first time within the context of a general election, was used by more than 1.7 million Canadians, 70% of whom were under the age of 45.52 Leading up to the 2019 election, more than two million users accessed the online voter registration service during the election period to check whether they were registered to vote, and more than 80,000 successfully added themselves to the lists. Of these, 75% (60,000 electors) were between the ages of 18 and 24.53

In its communication and awareness campaign for the 2015 general election, Elections Canada used social media for the first time to provide electors with information about registration and voting.54 According to the 2015 NYS, 40% of youth under the age of 35 used social media to share political information while only 29% of older adults did so.55 In August 2015, Elections Canada launched an election specific website to present its services to voters; the site received 16 million visits during the election campaign.56 The 2015 NYS also revealed that youth were most likely to use online sources of information during an election, whereas older adults were most likely to rely on television as their primary source of information.57

In 2019, Elections Canada worked with digital platforms Google, YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat and Twitter to produce more than a dozen online initiatives with the goal of driving electors to its website at elections.ca and online registration. The Facebook registration reminder (16 to 21 September 2019) generated 988,222 visits to the online registration service. Elections Canada also collaborated with Google to make sure that people searching for voting information using that search engine were directed to Elections Canada’s website at elections.ca. It also used its corporate social media accounts to interact with the public. Between 11 September and 22 October 2019, Elections Canada received 44,667 messages through its accounts and it responded to 2,696 enquiries.58

The Internet offers a wealth of information about political parties, their platforms and leaders. In their 2011 study on youth voter turnout, André Blais and Peter Loewen noted that “access to the internet makes the information acquisition required to vote in an election easier and is thus logically associated with higher participation.”59

Technology should not, however, be regarded as a panacea for increasing youth electoral engagement. Young people can be overwhelmed by the quantity and haphazard nature of information that is available on the Internet.

As for electronic voting, this method of casting ballots continues to pose technical challenges relating to authentication, security and privacy.60

Elections Canada sees raising awareness among young people before they reach voting age as a promising approach. Its parliamentary and electoral simulation exercises give young people their first exposure to the political process and introduce them to the basic aspects of parliamentary debate. The 2015 NYS revealed that 49% of voters below the age of 35 see voting as a duty, while 47% see it as a choice. In contrast, these proportions are 64% and 36% respectively among voters over the age of 35.61

In 2004, Elections Canada began supporting the Student Vote Program (SVP), which allows young people under the age of 18 to experience the federal electoral process through a parallel election at their school. Such parallel elections have been held as part of the SVP in every federal election since 2004. An evaluation of the program commissioned in 2011 by Elections Canada found that this program “has a significant positive impact on many factors associated with voter turnout, including political knowledge, interest and attitudes.”62 In conjunction with the 2021 general election, more than 800,000 students from nearly 6,000 schools, representing all 338 ridings, cast Student Vote ballots for candidates in their school’s riding; students also served as returning officers and poll clerks.63

In collaboration with federal and provincial partners, Elections Canada has developed a strategy to create civic education materials on elections for use by Canadian educators.64 Moreover, Elections Canada is renewing these materials, and according to the 2023–24 Departmental Plan, it expects to continue its work in this area..65 This initiative is consistent with the recommendations of many researchers who believe that greater emphasis should be placed on civic education programs in Canadian schools.66

There is little data in Canada about the amount of civics instruction in provincial school curricula. Comparisons are difficult because the methodologies used, the students’ ages and the number of hours devoted to civics courses differ from one jurisdiction to the next. Despite the lack of systematic evaluation of the impact of civic education on youth voter turnout in Canada, the research suggests that civic education does have a positive effect on future voter turnout.67 It is important to point out, however, that the ability of the federal government to intervene in educational matters is limited by the fact that the Constitution Act, 1867 gives the provinces nearly exclusive jurisdiction over this sector.68

The decline in turnout among those eligible to vote for the first or second time was first observed following the 1984 federal general election. Although the number of first- and second-time voters who exercised their right to vote increased substantially in the last two general elections, youth voter turnout remains lower than the turnout for all other age groups. Several studies of youth voter disengagement seem to indicate that the propensity to vote no longer increases with age, as was seemingly the case for previous generations.

The findings of more recent studies are not quite so alarmist, suggesting instead a delay in voter turnout among young people today resulting from their late transition to adult life compared with earlier generations. Other researchers believe that the disengagement may be temporary and may not continue.

In the available literature on the determinants of youth voter participation in Canada, there is no consensus regarding the socio-demographic factors that may be at play. Authors disagree, for example, on the subject of young people’s interest in politics. Some researchers suggest that present generations are less interested in politics than previous generations were, while others believe that interest varies from one youth subgroup to another, arguing that youth voters should not be viewed as a homogeneous whole. That being said, several authors seem to agree that Canadian born youth are much more likely to vote than youth born outside Canada. There also seems to be agreement that the youth voters of today are less knowledgeable when it comes to politics, are more distrustful of the system and have a less developed sense of civic duty than the generations that came before them.

© Library of Parliament