In September 2017, the Clerk of the Privy Council released a report entitled The next level: Normalizing a culture of inclusive linguistic duality in the Federal Public Service workplace, in which he made a number of recommendations, including one to repurpose the bilingualism bonus to establish a new fund that would be used exclusively for the development of public servants’ language skills.1 The publication of this report has reignited debate about the bonus.

This Background Paper describes the purpose of the bonus and uses archival documents, House of Commons debates and newspaper articles to trace the history of the bonus from its introduction and development to the present day, and to summarize its financial impact.

The bilingualism bonus is a taxable fixed amount of $800 paid annually to employees of all departments, Crown corporations and separate agencies listed in schedules I, IV and V of the Financial Administration Act.2

Aside from some exceptions,3 employees are eligible for the bonus if they are in a designated bilingual position and have Second Language Evaluation results confirming that they meet the position’s language requirements.4

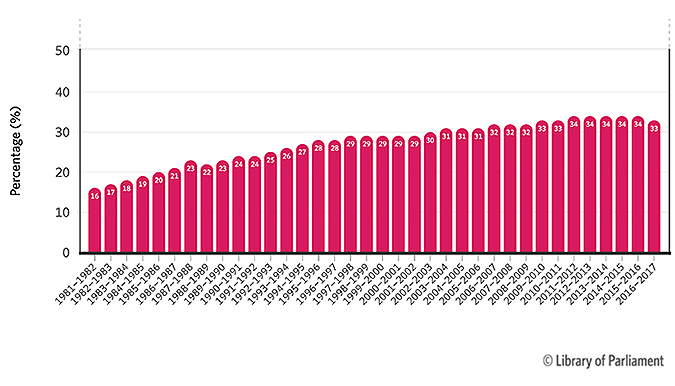

Figure 1 shows the proportion of public servants who were paid the bilingualism bonus relative to the overall federal public service workforce since 1981‑1982.

Figure 1 – Proportion of Bilingualism Bonus Recipientsa Relative to the Entire Federal Public Service,b 1981‑1982 to 2016‑2017

Notes:

The data shows that, in 1981‑1982, 16% of public servants were eligible for the bilingualism bonus. This percentage increased slightly each year, except in 1988‑1989 and 1996‑1997, when it declined by 1%. The proportion of public servants who received the bonus remained constant at 29% from 1997‑1998 to 2001‑2002 and then passed 30% in 2002‑2003. After a period of relative stability, the percentage of public servants receiving the bonus reached 34% from 2011‑2012 to 2015‑2016, before dropping to 33% in 2016‑2017.

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data provided by the Treasury Board Secretariat in April 2018 in tables entitled Bilingualism Bonus in the Federal Public Service, Total Amounts Paid and Number of Recipients (1981‑1982 to 2016‑2017), and Bilingualism Bonus, and Bilingual Positions in the Federal Public Service (1981‑1982 to 2016‑2017).

The bonus is governed by the Bilingualism Bonus Directive and is an integral part of the collective agreements between the parties represented on the National Joint Council.5

The concept of additional compensation for proficiency in English and French dates back to the 19th century, when employees who could write in English and French received an annual supplement.6 However, it was in the political and sociocultural context of the 1960s that the first modern public service bilingualism bonus developed.

In the early 1960s, public service unions proposed giving federal public servants a bonus for working in their second official language, as fair compensation for becoming bilingual.

This proposal was put before Parliament by Louis-Joseph Pigeon, MP for Joliette‑L’Assomption‑Montcalm, and Conservative Party critic for public works. On 2 October 1963, Mr. Pigeon tabled in the House of Commons Bill C‑96, An Act Respecting Employment of Bilingual Persons in the Public Service and in Crown Corporations, which would

provide for the suppression, within the civil service and the crown corporations, of the discrimination which marks at the present time the hiring and employment of French speaking personnel, and it would give preference to bilingual candidates.7

Bill C-96 died on the Order Paper. On 20 February 1964, Mr. Pigeon reintroduced his bill as Bill C‑34. It was debated on 9 June 1964 and subsequently died on the Order Paper.

The government of Lester B. Pearson, which held power from 1963 to 1968, did not support a bilingualism bonus, maintaining that language skills were one of the core competencies and were already reflected in public servants’ compensation.8

In February 1965, the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism (also known as the Laurendeau-Dunton Commission) released a preliminary report describing Canada as a nation in crisis where the two majorities – anglophone Canada and francophone Quebec – were in conflict. The public service was not immune to the linguistic tensions described by the Commission:

In 1965, barely 9% of positions in the federal public service were designated bilingual; services were only offered in English; and Francophones made up just 21% of the workforce in federal institutions, despite representing around 28% of the Canadian population.9

On 6 April 1966, Prime Minister Pearson announced a policy in the House of Commons concerning bilingualism in the public service:

In respect of bilingual clerical and secretarial positions, it has been agreed in principle that a higher rate of pay will be paid in future in respect of clerical and secretarial positions in which there is the requirement for a knowledge of both languages and where both are used in the performance of duties, providing the incumbents of such positions meet standards of competence established by the Civil Service Commission.10

On 9 February 1967, the Treasury Board officially established the bilingualism bonus.11 The government announced that public servants in the secretarial, stenographic and typing groups who worked in their second language at least 10% of the time were to receive a bonus equivalent to 7% of their pay. They also had to take a test to assess their language skills.12

With the coming into force in 1969 of the first Official Languages Act, the government continued to implement its bilingualism program within the public service and, as part of the Parliamentary Resolution on Official Languages in the Public Service of Canada passed in 1973, it reviewed the language designations of public service positions.

This review reopened the debate on the bilingualism bonus. The federal public service unions stepped up their campaign to make the 7% bonus available to all qualifying federal public servants. The government was against the applying the formula throughout the public service. It followed the guideline developed by the Laurendeau-Dunton Commission. In Book III of the final report, published in 1969, the commissioners stated that “[s]alary should not be determined by the bilingualism of the individual, but rather by the effective use of the two languages at work.”13

The situation escalated on 13 February 1975. Employees of the Unemployment Insurance Commission, based in Montréal, refused to serve the public in English. The Honourable Jean Chrétien, then president of the Treasury Board, stated that the government was not “projecting to extend this bonus to other categories of federal public servants.”14 The boycott of bilingual services ended when the government promised to resume negotiations.15

The government unveiled its new language of work policy in August.16 It also made a commitment to review the pay scale for designated bilingual positions.17 Although it did not agree to a bonus, in the fall of 1975 it agreed in principle to additional compensation.

Tensions continued to mount despite this commitment. The Quebec branch of the Public Service Alliance of Canada (PSAC) threatened to boycott services in English across Quebec if an agreement was not reached.18 Mr. Chrétien told the House of Commons that progress was slow because it was not simply a matter of reviewing the pay scale for designated bilingual positions in Quebec, but throughout Canada.19

Cabinet discussed the matter on 18 December 1975 and decided not to change course. It had to consider the policies of the Anti‑Inflation Board (AIB). The AIB had been established by an Act of Parliament in 1975 to administer a wage and price control program. Cabinet informed the Treasury Board President that he should “not formally request the Anti‑Inflation Board to provide a ruling on the question of compensation for the provision of bilingual services.”20 Instead, Cabinet wanted him to

continue discussions with the union with a view to ascertaining agreed union position; continue to implement the previously-agreed policy of designating bilingual positions and negotiating appropriate compensation with respect thereto, taking cognizance of the effect of the requirement of a bilingual capacity in adding to job complexity.21

By late January 1976, despite the previous Cabinet decision, Jean Chrétien informed the unions that the Treasury Board was willing to present an official submission to the Anti‑Inflation Board in cooperation with the unions.22 The Treasury Board President based his decision on

the informal and preliminary opinion of the Anti‑inflation Board that any newly‑granted extra compensation received by public service employees in respect of bilingual capability would be deemed to be an income increase subject to the anti‑inflation guidelines.23

By asking the AIB to rule on the bonus, Chrétien believed he could offer the bilingualism bonus to the unions while specifying that future pay raises would have to be reduced accordingly to ensure compliance with the directives. He expected labour organizations to reject the bonus under these circumstances, and the government would no longer face pressure from bilingual public servants.24

On 15 March, the AIB reached an unexpected decision: it ruled that the directives did not apply to the compensation in question because it had been the subject of a specific ruling prior to 14 October 1975,25 the date on which the AIB was officially established.

On 9 September 1977, following further clashes with PSAC,26 the federal government agreed to pay an annual fixed amount of $800 to public servants who met the language requirements of their position.

On 15 October 1977, Treasury Board officially established the bilingualism bonus system that is still in effect to this day.27

The bilingualism bonus was supposed to be eliminated in 1983, as it had only been meant as a temporary measure to support bilingual staffing. In August 1978, the government of Pierre Elliot Trudeau announced that the bonus would be terminated as of 31 March 1979, but a series of political events forced the government to continue the program.

The proposal to end the bilingualism bonus was brought before the Public Service Staff Relations Board, an administrative tribunal, which ruled in 1979 and 1980 that the bonus constituted a legitimate pay supplement for using the additional language skills required by a position and that it was subject to collective bargaining. Dissatisfied, the government appealed the Board’s ruling but in 1981, it was upheld by the Federal Court of Appeal, which found the matter to be within the Board’s jurisdiction.28

The government clarified the criteria for the program in the 1980s.29 On 16 January 1987, a new milestone was reached: Treasury Board issued the Bilingualism Bonus Directive. From that point onward, the bonus would be an integral part of collective agreements.

The bilingualism bonus was brought before the courts in the early 1990s in Gingras v. Canada. The Federal Court ruled that non‑public service employees of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) are entitled to the bilingualism bonus because the Treasury Board is their employer.30 The government appealed, but the Federal Court of Appeal upheld the lower court’s decision on 10 March 1994.31 The government announced in May 1994 that it would abide by the ruling.32

In 2006, 119 employees and former employees of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) asked the Federal Court to review the CSIS director’s decision not to grant them the bilingualism bonus. Fifteen years earlier, in Gingras v. Canada, the Federal Court had ruled that CSIS was not under the responsibility of Treasury Board, and the director of CSIS could therefore exercise discretion regarding payment of the bilingualism bonus. However, the plaintiffs were all employed by the RCMP prior to the creation of CSIS in 1984. In Employé no 1 c. Canada, the Court quashed the decision by the CSIS director not to grant the bonus.33 In 2007, the Federal Court of Appeal dismissed an appeal from the decision.34 As a result, the employees and former employees obtained the right to the bilingualism bonus. It is worth noting that, on 1 April 2013, CSIS eliminated the bonus for its non-unionized employees.35

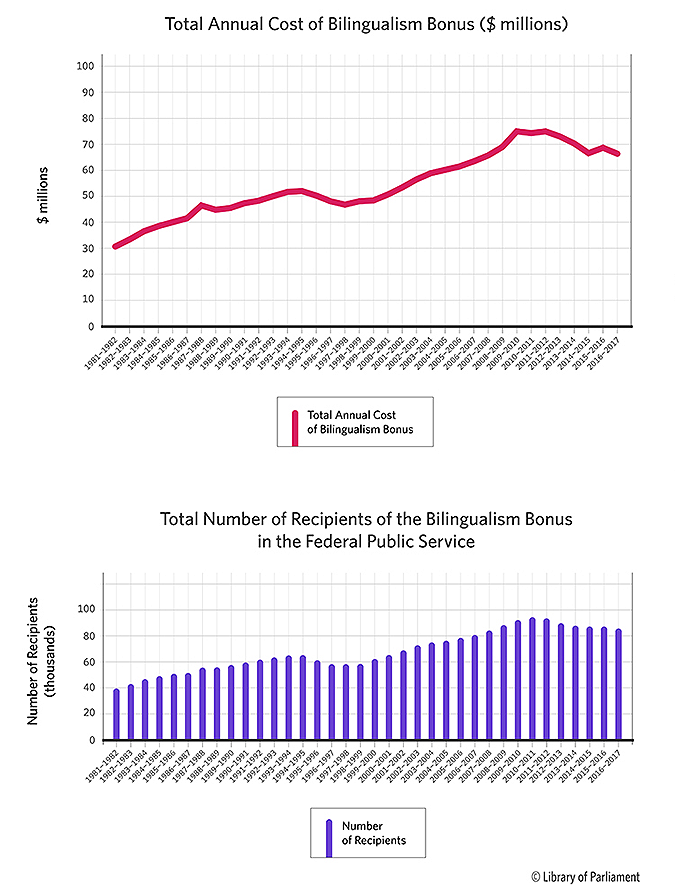

In April 2018, the Library of Parliament obtained a complete, unpublished dataset on the total cost of the bilingualism bonus for fiscal years 1981‑1982 to 2016‑2017 from the Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS). A summary of this data is provided in Figure 2. Note that the total annual cost and total number of recipients for years prior to 1997‑1998 are estimates based on the number of active employees deemed eligible for the bilingualism bonus, as this data could not be extracted from the salary payment and deduction files.

Figure 2 – Total Annual Cost and Number of Recipients of the Bilingualism Bonus in the Federal Public Service, 1981‑1982 to 2016‑2017

Note: The data from years prior to 1981‑1982 are not included for data quality reasons.

The first graph of Figure 2 shows the change in the total annual cost of the bilingualism bonus in millions of dollars. In 1981‑1982, the bonus cost over $30 million and the total cost rose gradually thereafter.

The total cost increased notably in fiscal year 1986‑1987, reaching over $46 million in 1987‑1988. After that, the total cost of the bonus generally trended upward. It reached $52 million in 1994‑1995, but subsequently declined to $46.6 million in 1997‑1998, about what it had cost 10 years earlier. The total cost of the bonus then rose again, peaking in 2011‑2012 at $74.8 million. Total annual spending on the bonus declined after that. In 2016‑2017, it cost over $66 million.

The second graph of Figure 2 shows the change in the total number of federal public servants who received the bilingualism bonus. Overall, the number of recipients rose steadily to a high of 65,000 in 1994‑1995. That figure declined from 1995‑1996 to 1997‑1998. After that, the number of recipients increased again, peaking in 2010‑2011 at 94,000. The number of recipients gradually declined thereafter. In 2016‑2017, the total was over 85,000.

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data provided by the Treasury Board Secretariat in April 2018. The data cover employees of core public administration departments and agencies and separate agencies, as listed in schedules I, IV and V of the Financial Administration Act, R.S.C., 1985, c. F-11. Civilian employees of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police are included in the data, but only those who were part of the core public administration. The data do not cover employees of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service, the National Capital Commission, Canada Investment and Savings, the Canadian Forces Non‑Public Funds, and the Security Intelligence Review Committee.

According to the TBS data, the bilingualism bonus program cost over $30 million in 1981‑1982. The cost of the bonus increased gradually thereafter.

As mentioned above, after the Bilingualism Bonus Directive was adopted in January 1987, the bonus became part of collective agreements. It is possible that this change contributed to the increase in the number of recipients: from 1986‑1987 to 1987‑1988, that figure increased by 8% (or by 4,135 public servants).

In April 1987, TBS imposed language proficiency tests on bilingualism bonus recipients.36 According to the Commissioner of Official Languages, this new measure resulted in some recipients losing the bonus. However, the Commissioner noted that these public servants could become eligible for the bonus again by taking up to 200 hours of additional language training.37 All told, the number of recipients did increase from 1987‑1988 to 1988‑1989, but only by 0.38% (209 recipients).

Although the number of recipients increased slightly between 1987‑1988 and 1988‑1989 (from 55,706 to 55,915), the total cost of the bonus declined marginally to $44.8 million. According to TBS, some years have 27 pay periods. This was the case in 1987‑1988, and that is why the cost of the bonus was higher that year than it was in 1988‑1989, despite the lower number of recipients as of the end of March.38 The total cost of the bonus increased the following year and continued to do so gradually throughout the 1990s. It reached a little over $52 million in 1994‑1995.

Figure 2 does not account for the additional expenditure of an estimated $33 million in 1994‑1995 as a result of the Federal Court of Appeal ruling in Gingras v. Canada39 (see section 3.4 of this Background Paper).40 The Commissioner of Official Languages reported that the total cost of the bonus was therefore $86.6 million in 1994‑1995, taking into account the “$33 million to cover retroactive payments which had to be made to 2,500 officers of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.”41

From 1994‑1995 to 1997‑1998, the cost of the bonus gradually decreased. The Commissioner of Official Languages reported that the decrease was the result of “departures that occurred following government downsizing.”42 The total cost of the bonus fell from $52 million (65,239 recipients) in 1994‑1995 to $46.6 million (58,318 recipients) in 1997‑1998.

Starting in 1998‑1999, the total cost of the bilingualism bonus program, along with the number of recipients, rose, before stabilizing in 2009‑2010 at just over $74.8 million. The next fiscal year, the total cost of the bonus program began a gradual decline owing to workforce reductions across the public service and the consequent decrease in the number of recipients. This downsizing of the federal workforce was part of the 2011 Deficit Reduction Action Plan and the 2011‑2012 Strategic and Operating Review.

In 2016‑2017, the total cost of the bonus was slightly more than $66 million.

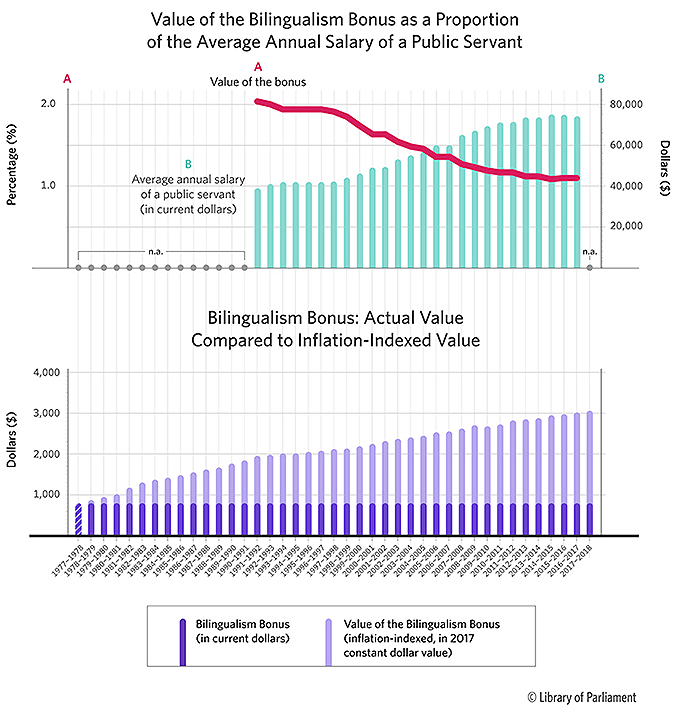

The annual fixed amount of $800 was established in 1977 and has never been increased. As shown in Figure 3, if this initial amount had been indexed to inflation, the bilingualism bonus would now be worth approximately $3,060.

Figure 3 – Actual and Indexed Value of the Bilingualism Bonus 1977‑1978 to 2017‑2018

The first graph of Figure 3 shows the decrease in the value of the bilingualism bonus relative to the average annual salary of a public servant between 1991‑1992 and 2017‑2018. While the bilingualism bonus was worth a little over 2% of the average public servant salary in 1991, it had fallen to 1% of that value in 2016‑2017.

The second graph compares the actual value of the bilingualism bonus with its inflation‑indexed value (in constant 2017 dollars). The bonus was introduced at $800 in 1977, and that amount has never changed. Had it been indexed, the bonus would be worth just over $3,000 today.

Sources: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from Bank of Canada, Inflation Calculator; and Statistics Canada, “Table: 14-10-0244-01: Average weekly earnings (SEPH), unadjusted for seasonal variation, by type of employee for selected industries classified using the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS)”; and “Table 14-10-0203-01: Average weekly earnings by industry, monthly, unadjusted for seasonality,” accessed 1 May 2018.

When the bilingualism bonus program was introduced in 1977, Max Yalden, the Commissioner of Official Languages at the time, was extremely opposed to it and called for its cancellation. All subsequent commissioners have questioned its effectiveness as a means of developing a bilingual public service and ensuring that services are delivered in both official languages. Generally speaking, they have stated that language skills are core competencies that should be reflected in public servants’ compensation. A number of commissioners have stated that the funds should be allocated to language training and, more recently, that the annual fixed amount of $800 is not an incentive to learn or master a second official language.

In 2005, as part of a study on bilingualism in the public service, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Official Languages examined the bilingualism bonus. In its final report, the Committee recommended that the bonus be eliminated and that “knowledge of the two official languages be considered a professional skill that is reflected in the salaries of federal employees.”43 In its response to this recommendation, the government stated that since

the National Joint Council Bilingualism Bonus Directive forms part of the collective agreements, the bilingual bonus could not be amended without consulting the bargaining agents participating on the National Joint Council.44

Finally, as stated above, the Clerk of the Privy Council released a report in September 2017 recommending that the bilingualism bonus be repurposed to establish a fund for the development of public servants’ language skills, to be administered jointly with bargaining agents.45

† Library of Parliament Background Papers provide in-depth studies of policy issues. They feature historical background, current information and references, and many anticipate the emergence of the issues they examine. They are prepared by the Parliamentary Information and Research Service, which carries out research for and provides information and analysis to parliamentarians and Senate and House of Commons committees and parliamentary associations in an objective, impartial manner. [ Return to text ]

© Library of Parliament