The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates that more than 2.9 million refugees are currently in need of resettlement to a third country. These are refugees who, according to the UNHCR, can neither return to their country of origin nor integrate into their country of first asylum. A total of 158,700 refugees were resettled worldwide in 2023, both with and without UNHCR assistance. Canada is among the top countries in the world in terms of refugee resettlement.

Canada’s resettlement programs offer three main streams through which refugees enter Canada:

The PSR program is considered a “complementary pathway” as it is an alternative means by which refugees can resettle in a third country. This program has been successful in resettling large numbers of refugees, and as a result, the Government of Canada has partnered with the UNHCR and other organizations in the Global Refugee Sponsorship Initiative (GRSI). The GRSI is an international project that shares best practices with other countries interested in implementing a private refugee sponsorship model. Since its launch at the end of 2016, different variants of community sponsorships have begun across the world.

Other complementary pathways include the Student Refugee Program offered through World University Service of Canada, which combines resettlement with international student programs at Canadian universities, colleges and CEGEPs. Additionally, the Economic Mobility Pathways Pilot introduces skilled refugees to Canada through an economic immigration stream.

The federal government has prioritized the resettlement of special groups such as women at risk, human rights defenders and LGBTQI+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex or other sexually or gender diverse) refugees. Other priority groups targeted by special government resettlement initiatives in recent years include Afghan refugees in 2021 and Sudanese refugees fleeing civil war in 2023.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates that more than 2.9 million refugees are currently in need of resettlement in a third country.1 These are refugees who, according to the UNHCR, can neither return to their country of origin nor integrate into their country of first asylum. The international community resettled 158,700 refugees in 2023, both with and without UNHCR assistance.2

In 2023, Canada resettled 51,081 refugees, second only to the United States’ 75,100.3 Each year, Canada accepts a portion of its new permanent residents as refugees resettled from abroad. In the last decade, this portion has been as low as 5% (2014 and 2020) and as high as 10.8% (2023). Current planned levels for refugee resettlement between 2025 and 2027 will maintain 2023 levels, although overall numbers each year will decline slightly.4

Since 2017, most refugees resettled to Canada enter under private sponsorship rather than as government-assisted refugees. As a result of the success of the private sponsorship program, the Government of Canada, in partnership with the UNHCR and others, spearheads the Global Refugee Sponsorship Initiative (GRSI), an international project sharing best practices with other countries interested in implementing a private refugee sponsorship model.

Canada’s immigration policy is shaped by the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act,5 which states that Canada’s refugee program is primarily a means of saving lives by offering protection to those who need it and aiding the international effort to help those in need of resettlement. Since 2018, Canada has actively participated in initiatives related to the United Nations (UN) Global Compact on Refugees (GCR),6 supporting its objectives of easing the burden on refugee host countries and promoting third-country solutions for refugees. In addition to resettlement, Canada has international obligations to those who come to Canada on their own and need protection (asylum seekers).7

This Hill Study provides an overview of Canada’s refugee resettlement programs, and outlines eligibility for resettlement and the different programs in place for resettlement in Canada. It also discusses the role that resettlement plays in international agreements like the GCR and examines Canada’s role in the GRSI. The paper concludes with a consideration of some of the challenges regarding refugee resettlement in the current Canadian context.

To be eligible for resettlement in Canada, a refugee must be referred by the UNHCR, another designated referral organization or a private sponsorship group. Referred individuals can be from two classes, either the Convention Refugees Abroad class (Convention refugees) or the Country of Asylum class. Convention refugees meet the criteria of the 1951 UN Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol: they must have a well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group or political opinion. They must also be outside of their country of nationality or habitual residence and be unable to find protection there.

Country of Asylum refugees are those who, according to the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations, are “seriously and personally affected by civil war, armed conflict or [a] massive violation of human rights” and are “outside all of their countries of nationality and habitual residence.”8 The regulations also state that the applicant must not be awaiting, within a reasonable period, a durable solution in a country other than Canada.9 Finally, the applicant must meet security and criminality admissibility criteria, followed by a public interest criteria medical examination to screen for any medical conditions likely to be a danger to public health or safety in Canada.10

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) visa officers stationed overseas generally determine if an individual is eligible for resettlement and admissible to Canada. Some refugees are referred to IRCC for consideration by a designated referral organization (primarily the UNHCR), while others are referred by private sponsors. Applications are considered individually, except where the mass movement of refugees (i.e., as a result of conflicts or generalized violence) has caused the UNHCR to declare a group prima facie refugees.11 An example of prima facie refugees were Syrians fleeing the civil war in their country who were resettled to Canada in 2015.

Refugees are resettled to Canada through one of the following programs:

Under the 1991 Canada–Québec Accord relating to Immigration and Temporary Admission of Aliens,15 the Quebec government selects refugees from the pool of IRCC-approved cases for resettlement and administers its own private sponsorship program.

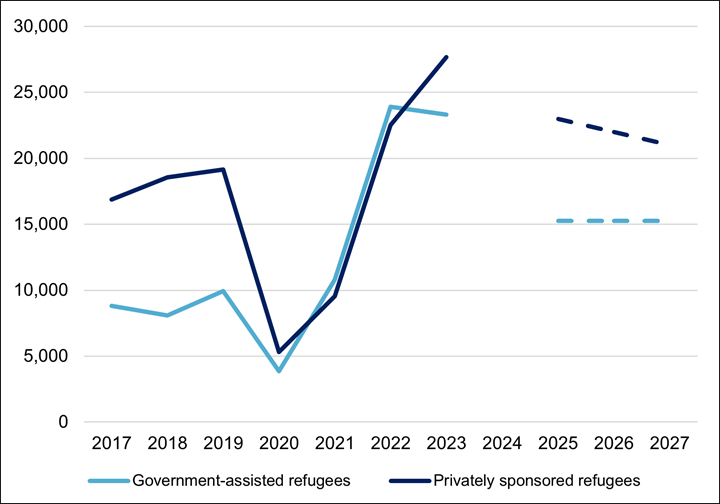

In 2017, IRCC began making a multi-year immigration levels plan, allowing those working with newcomers to plan beyond one year. The current plan projects an overall decline in immigration levels between 2025 and 2027, with a corresponding decline in the level of resettled refugees. While the numbers for the GAR and BVOR programs are projected to remain constant, those for the PSR program decrease by 1,000 each year.16

The federal government bears complete responsibility for refugees who arrive through the GAR program. IRCC’s Resettlement Assistance Program (RAP) provides settlement support for government-assisted refugees through a network of service provider organizations. This support includes the following:

Eligible refugees may also receive income assistance through RAP to cover start-up and ongoing costs, usually for the first year in Canada.17

Some refugees selected for resettlement by the government need special assistance, so the government works with private sponsors to meet their needs for a longer settlement period through the JAS program. A refugee may qualify for the JAS program for a variety of reasons, some of which include:

The PSR program is unique among resettlement programs in that sponsors may refer refugees for resettlement to IRCC. The sponsors assume all the financial costs for the initial resettlement period of 12 months.

In the PSR program, private sponsors provide initial settlement support like that provided by RAP, as well as emotional and social support. In 2023, the estimated cost for sponsoring a single individual was $16,500, while the cost of sponsoring a family of six was $35,500.18 These estimates have not changed since May 2018.19 The PSR program’s reliance on private resources allows refugees to be resettled in Canada without significant increases in government funding.

Private sponsors in the PSR program include:

While refugee resettlement dipped significantly at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the rates of both GARs and PSRs climbed rapidly through the following years, as shown in Figure 1. The planned immigration levels between 2025 and 2027 (presented as dashed lines in the graph to show projections) show an overall decrease in both GARs and PSRs, a response to the fact that “[d]emand for the … program has long outpaced annual admission spaces, resulting in large inventories and long processing times.”21 This was kickstarted by the federal government’s announcement in November 2024 of a temporary pause (until 31 December 2025) on new applications from Groups of Five and Community Sponsors under the PSR program.22 This is further discussed in section 6.2 of this HillStudy (“Current Challenges”).

Figure 1 – New Permanent Residents Admitted Through the Government-Assisted Refugee Program and the Private Sponsorship of Refugees Program, 2017–2023 and Immigration Levels Plan Targets, 2025–2027

Note: At the time of writing, no data was available for 2024.

Sources: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament based on data obtained from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), “Table 4: New Permanent Residents Admitted in 2017,” 2018 Annual Report to Parliament ![]() (3.5 MB, 35 pages), 2018, p. 40; IRCC, “Table 4: Permanent Residents Admitted in 2018,” Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration 2019

(3.5 MB, 35 pages), 2018, p. 40; IRCC, “Table 4: Permanent Residents Admitted in 2018,” Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration 2019 ![]() (1.7 MB, 44 pages), 2020, p. 38; IRCC, “Table 4: Permanent Residents Admitted in 2019,” 2020 Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration; IRCC, “Table 4: Permanent Residents Admitted in 2020,” 2021 Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration; IRCC, “Table 4: Permanent Residents Admitted in 2021,” 2022 Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration; IRCC, “Table 4: Permanent Residents Admitted in 2022,” 2023 Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration; IRCC, “Table 3: Permanent Residents Admitted in 2023,” 2024 Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration; and Government of Canada, “Permanent Residents,” Notice – Supplementary Information for the 2025–2027 Immigration Levels Plan, 24 October 2024.

(1.7 MB, 44 pages), 2020, p. 38; IRCC, “Table 4: Permanent Residents Admitted in 2019,” 2020 Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration; IRCC, “Table 4: Permanent Residents Admitted in 2020,” 2021 Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration; IRCC, “Table 4: Permanent Residents Admitted in 2021,” 2022 Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration; IRCC, “Table 4: Permanent Residents Admitted in 2022,” 2023 Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration; IRCC, “Table 3: Permanent Residents Admitted in 2023,” 2024 Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration; and Government of Canada, “Permanent Residents,” Notice – Supplementary Information for the 2025–2027 Immigration Levels Plan, 24 October 2024.

Some critics of the PSR program have voiced concerns that it allows the federal government to shift the responsibility it has towards international refugees to the private sector, privatizing resettlement.23 This critique stems in part from the way in which refugees for each program are selected – those in the GAR are referred by the UNHCR on the basis of vulnerability, and those in the PSR program are often chosen because of their existing links with Canadian society, its citizens and permanent residents.24 Others have pointed out that the program often serves as a means of family reunification rather than for assisting those most in need, and that such a situation calls into question the humanitarian aim of Canada’s resettlement program.25

The BVOR program is a partnership program that began in 2013 as a cost-sharing measure between IRCC, refugee referral organizations26 and private sponsors (Sponsorship Agreement Holders, Groups of Five and Community Sponsors). The program matches private sponsors with refugees who have already been referred to IRCC by an organization and approved for resettlement. Refugees referred by Groups of Five and Community Sponsors must have documentation showing that the UNHCR or a foreign government has officially recognized their refugee status.27 The costs of sponsorship are shared between the government and private sponsors, with RAP providing the initial six months of financial support and private sponsors covering the start-up costs and an additional six months of financial support. Private sponsors provide the entirety of the settlement support. The BVOR program represents a minority of Canada’s resettled refugees, with targets of 100 per year set for 2025–2027.28 This continues a trend of decreasing numbers of people arriving through the BVOR program over time since 4,420 entered in 2016.29

A government evaluation of the BVOR program noted several challenges. These included low uptake of the program and uncertain cost-saving benefits.30

Table 1 below summarizes the main differences between the various resettlement programs.

| Program | Referred to Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada By | Funded By | Duration of Funding Support | Settlement Support Provided By | Planned Level of Admissions in 2025 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Government-Assisted Refugees (GAR) Program | United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and other designated referral organizations | Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), through the Resettlement Assistance Program (RAP) | 12 months | IRCC, through RAP | 15,250 |

| Joint Assistance Sponsorship Program under GAR | UNHCR and other designated referral organizations | IRCC, through RAP | 24 months | Private sponsors | n/a |

| Private Sponsorship of Refugees Program | Private sponsors | Private sponsors | 12 months | Private sponsors | 23,000 |

| Blended Visa Office–Referred Program | UNHCR and other designated referral organizations | IRCC and private sponsors jointly; sponsors pay start-up costs | 6 months –IRCC; 6 months –private sponsors | Private sponsors | 100 |

Sources: Table prepared by the Library of Parliament using information obtained from Government of Canada, Government-Assisted Refugees program; Government of Canada, Joint Assistance Sponsorship; Government of Canada, How to sponsor a refugee; Government of Canada, Partners in Refugee Resettlement: Blended Visa Office–Referred Program; and Government of Canada, “Permanent Residents,” Notice – Supplementary Information for the 2025–2027 Immigration Levels Plan, 24 October 2024.

In recent decades, international migration has increased substantially. This reality prompted the international community to design cooperative mechanisms for managing and protecting migration flows. The results are the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration32 and the Global Compact on Refugees (GCR). Both global compacts build on the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals33 and the 2016 New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants. This declaration outlined an initial set of voluntary commitments that UN member states adopted to strengthen and enhance mechanisms to protect refugees and migrants and to pledge support for host countries. The global compacts are non-binding, instead providing incentives to garner states’ participation.

The GCR espouses four central objectives:

In terms of Canada’s international priorities, the GCR provides a means of continuing to advocate for gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls.34 The GCR also strengthens collective security by preserving a rules-based order that respects human rights.

As a global leader on refugee policy, Canada has also been a leader in promoting the global compacts, garnering recognition and influence worldwide. However, some scholars have argued that since signing on to the global compacts in 2018, Canada has used them to advance its own foreign policy interests.35 They point out that few, if any, changes to Canada’s laws, policies or programs have been enacted in an effort to more closely align them with the precepts of the global compacts.

Resettlement of refugees to Canada includes both formal resettlement programs and what are known as “complementary pathways” that provide alternative, regulated immigration routes for refugees to a third country. Canada’s PSR program is a complementary pathway that has served as a model that other countries have since adopted in the spirit of the GCR. Other routes available to refugees include entry to a Canadian university through sponsorship by World University Service of Canada (WUSC) and opening economic immigration pathways to refugees.

The Global Refugee Sponsorship Initiative (GRSI) brings together the Government of Canada, the UNHCR, the University of Ottawa, the Open Society Foundations, the Giustra Foundation and the Shapiro Foundation to increase refugees’ access to complementary pathways to third countries by working with these countries to design their own community refugee sponsorship programs. Canada’s PSR program, as discussed above, has proven successful in sponsoring and integrating large numbers of refugees while keeping government costs of sponsorship to a minimum.

The GRSI’s objectives are as follows:

Since the GRSI’s launch at the end of 2016, different variants of community sponsorships have begun across the world. Programs have been launched in Argentina, Australia, Belgium, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States, with additional short-term programs elsewhere.36 While Canada’s PSR program is offered as a model through the GRSI, each country’s approach is unique, and there is substantial variation between the programs.

The Student Refugee Program offered through WUSC has combined resettlement with international student programs at Canadian universities, colleges and CEGEPs since 1978. WUSC is an official Sponsorship Agreement Holder through the PSR program, bringing in more than 130 refugees as permanent residents to Canada each year to study. One of the noted strengths of this program is the natural means of integration that student and campus life offer new refugees, with language skills development, social networks and work opportunities built into the student experience.37

The Economic Mobility Pathways Pilot (EMPP), initially launched as a feasibility study in April 2018, began with the intention to resettle 10 to 15 refugees that met the requirements for Canada’s economic immigration programs. Over the years, it has grown into a pathway for skilled refugees to come to Canada, addressing the needs of both global refugee resettlement and Canada’s labour market. The government announced an expansion to the program in 2022 and committed in 2023 to make the program permanent by 2025.38 Nonetheless, the EMPP has yet to be made permanent and is currently set to expire in June of 2025.39 IRCC’s 2025–2027 Immigration Levels Plan calls for a reduction in admissions through all federal economic pilots, including the EMPP, in both 2026 and 2027.40

The UNHCR refers refugees for resettlement who are deemed at risk in their host country or who have particular needs or vulnerabilities. In other cases, a lack of foreseeable solutions for whole population groups may result in the UNHCR referring refugees collectively for resettlement.41 The UNHCR and the international community recognize that resettlement spaces should be given to both individuals experiencing urgent unfolding conflicts and those in protracted refugee situations who have been displaced for many years.

The Government of Canada sets its own priorities for refugee resettlement by identifying specific vulnerable groups and refugee populations. IRCC states that it prioritizes refugees based on factors that overlap to a large degree with those of Gender-based Analysis Plus, like race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership in a particular social group.42 For example, women refugees have been a long-standing priority for resettlement, beginning in 1988 when IRCC introduced the Women at Risk program (now the Assistance to Women at Risk program). According to IRCC, the program “provides resettlement opportunities to women who are in precarious or permanently unstable situations abroad.”43 Eligible candidates can enter through any of the resettlement programs. Additionally, the government has prioritized LGBTQI+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex and other sexually or gender diverse) refugees for resettlement. Since 2011, the Rainbow Refugee Assistance Partnership has blended government and private support to sponsor refugees fleeing persecution due to their sexual orientation or gender identity.44 These refugees enter through the PSR program.

In 2021, the Government of Canada introduced a dedicated stream for human rights defenders and their families within the GAR program. The number of spaces was doubled to 500 in 2023, and Front Line Defenders and ProtectDefenders.eu were named as designated refugee referral organizations.45

In the past decade, the GAR program has evolved considerably in terms of the numbers and types of refugees prioritized for resettlement. IRCC describes its new operational environment as one in which it is increasingly called upon to implement immigration responses to support a foreign policy of assisting populations facing humanitarian crises.46 For example, when Afghanistan fell to the control of the Taliban in 2021, the Government of Canada announced a special measure to resettle 20,000 Afghans, a target that was later increased to 40,000.47 Likewise, after the renewal of civil war in Sudan in 2023, the government pledged to resettle 4,000 refugees through the GAR program and 700 through the PSR program.48 However, these humanitarian commitments can ultimately put pressure on the existing resettlement program.

As noted in section 3.2 of this paper, the PSR program presents some specific challenges in terms of resettlement priorities. Sponsored refugees are selected privately, often based on factors such as existing family in, or community ties to, Canada. Some critics fear that this tends to favour refugees from a handful of regions of the world to the detriment of others where refugees are also in need of resettlement.49

The refugee resettlement programs face backlogs and lengthy processing times. IRCC reported on 31 January 2024 that there were 112,900 PSR and GAR applications in its inventory, with average processing times of 41 months and 27 months, respectively.50 Data provided to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Accounts in 2023 breaks this backlog down by program: at the end of October 2023, the processing inventory held 25,640 GAR applications and 71,180 PSR applications.51 The heavy backlog faced by the PSR program has led to growing processing times, prompting the federal government’s pause on new applications from Groups of Five and Community Sponsors from 29 November 2024 until at least the end of December 2025. Both the PSR and GAR programs require visa officers to conduct in-person interviews and medical and security assessments with referred refugees, and this can be delayed further by the prevailing security conditions in the refugee’s country of temporary residence.52

In recent years, LGBTQI+ refugees, among others, have raised concerns regarding some of the operational difficulties faced by those who find themselves in a country of asylum where they are unable to be recognized as refugees or be given protection. This may occur for a range of political or cultural reasons. In the case of LGBTQI+ individuals, their identities and activities are criminalized in many countries, and thus their ability to gain refugee status based on being LGBTQI+ is likewise negatively affected.53 While the UNHCR can provide refugee status determination and protection to those who need it when possible, UNHCR staff cannot provide guarantees that national laws of the country of asylum will not be applied to LGBTQI+ refugees, even if they contravene international human rights law.54 This negatively impacts the refugee’s ability to be recognized as such and referred for resettlement.

The federal government significantly reduced its planned immigration levels for 2025–2027, in direct response to increased concern expressed by Canadian citizens about the current rate of immigration. In 2021 and 2022, Canada welcomed record numbers of new permanent residents.55 However, public opinion surveys conducted by IRCC between March and November in 2023 found that the proportion of Canadians who deemed immigration levels too high rose by 13 percentage points, reaching its highest level in two decades.56 Nearly one-third of Canadians surveyed by the department regarding the 2024–2026 levels plan described the number of refugees as being too high, a significant increase from previous years.57

The 2025–2027 levels plan reduces intake into the PSR program and holds the levels in the GAR and BVOR programs steady. These changes have been sharply criticized by refugee advocates. The Canadian Council for Refugees condemned the plan by decrying the increased time potential sponsored refugees will have to wait to apply to come to Canada and pointing out that the GAR target is lower than in past years and fails to meaningfully address the global refugee crisis.58

Canada resettles very high numbers of refugees each year, in large part through its reliance on successful and innovative complementary pathways like the PSR program. With the number of refugees worldwide continuing to rise and Canadian attitudes towards immigration shifting, our resettlement programs will continue to be pulled in opposing directions. Canada’s ability to fulfil its international humanitarian commitments may increasingly rely on adopting creative solutions that embrace complementary pathways while seeking to emphasize the benefits that refugees can bring to their host communities.

As explained by the UNHCR,

[s]ituations of mass influx frequently involve groups of persons acknowledged as refugees on a group basis because of the readily apparent and objective reasons for flight. … The immediate impracticality of individual status determinations has led to use of a prima facie refugee designation or acceptance for the group.

UNHCR, Handbook on Procedures and Criteria for Determining Refugee Status and Guidelines on International Protection Under the 1951 Convention and the 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, February 2019, p. 104.

[ Return to text ]© Library of Parliament