Opioid‑related harms have reached crisis proportions in many countries, including Canada. Almost 23,000 Canadians died due to apparent opioid toxicity between January 2016 and March 2021. Many other people faced life‑threatening medical emergencies or other harms. These harms have been linked to many causes, including opioid‑prescribing practices and the presence of very potent opioids such as fentanyl and fentanyl analogues in the drug supply. The COVID‑19 pandemic has further worsened outcomes. The opioid crisis has touched Canadians from all walks of life, although it has not done so equally: people with certain identities, including men and Indigenous people, have been disproportionately harmed. In response to the crisis, the federal government has made investments and launched a variety of initiatives. Parliament has also addressed the issue by enacting legislation and proposing a range of other measures.

Opioids are substances with pain‑relieving properties. They include compounds extracted from opium poppy seeds and synthetic and semisynthetic compounds with similar properties and the ability to interact with opioid receptors in the brain.1

Opioids can refer to both approved prescription medicines and to illicit “street” (or non‑pharmaceutical) drugs. In Canada, pharmaceutical opioids are primarily prescribed to treat pain.2 Commonly prescribed opioids include codeine, oxycodone, hydromorphone, fentanyl, morphine and tramadol.3

However, opioid use can cause harm. Individuals who use opioids can experience long‑term adverse health outcomes, such as liver damage, increased tolerance (meaning that a larger dose is required to achieve the same effects), worsening pain or withdrawal symptoms, among others.4 Individuals can also use opioids in ways that are considered problematic, such as by using an opioid that was not prescribed to them or by using a prescribed opioid medicine in a manner other than as directed by a health professional, which can increase the risk of harm.5 Some people who use opioids develop opioid use disorder. Like other substance use disorders, opioid use disorder is a treatable medical condition, although many people face challenges in accessing treatment.6 If an individual takes too much of an opioid, they may experience breathing difficulties, unconsciousness or death.7 In Canada and other countries, opioid‑related harms have reached crisis proportions.8

This HillStudy offers an introduction to selected health aspects of the opioid crisis in Canada. It includes some key statistics, considerations related to the impact of the crisis on different groups of people, and information about recent federal initiatives and activities in the Parliament of Canada intended to address the crisis.

There has been a considerable increase in the use of prescription opioids since the 1980s. Increased prescription use has been followed by more reports of harms associated with prescription opioid use and an increased rate in the use of non‑prescription opioids. By 2016, eight Canadians were dying from opioid‑related toxicity each day.9 The opioid crisis can be measured in many ways. The sections below highlight a few national statistics, which, while not exhaustive, constitute a starting point for understanding the scope and nature of the opioid crisis in Canada.

The federal–provincial/territorial Special Advisory Committee on the Epidemic of Opioid Overdoses publishes data on some opioid‑related harms, including deaths. Approximately 22,828 people in Canada died due to apparent opioid toxicity between January 2016 and March 2021. In the first quarter of 2021 alone, 1,772 Canadians died of apparent opioid toxicity.10

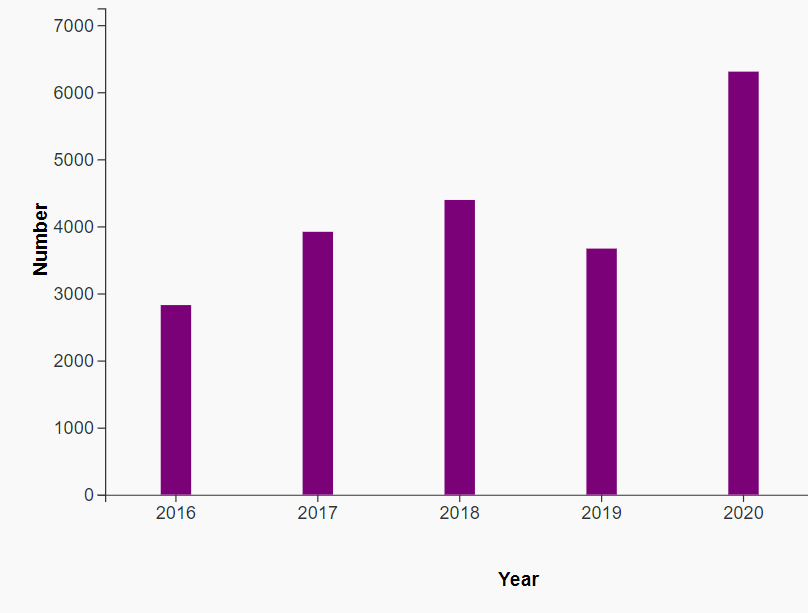

The annual total of apparent opioid toxicity deaths in Canada has increased over time, as shown in Figure 1. In 2020, 6,306 people died of apparent opioid toxicity, which is an average of about 17 deaths per day. Between 2018 and the first quarter of 2021, over half of opioid deaths also involved a stimulant.11 However, the trends have been different for accidental apparent opioid toxicity deaths and intentional (suicide) apparent opioid toxicity deaths. While deaths from accidental apparent opioid toxicity deaths have increased, the annual number of deaths from intentional apparent opioid toxicity has decreased each year between 2017 and 2020.12

Figure 1 – Annual Total of Apparent Opioid Toxicity Deaths in Canada, 2016–2020

Source: Government of Canada, “Graphs: Number of total apparent opioid toxicity deaths in Canada, 2016 to 2021 (Jan to Mar),” Opioid‑ and Stimulant‑related Harms in Canada (September 2021), Public Health Infobase, Database, accessed 19 October 2021.

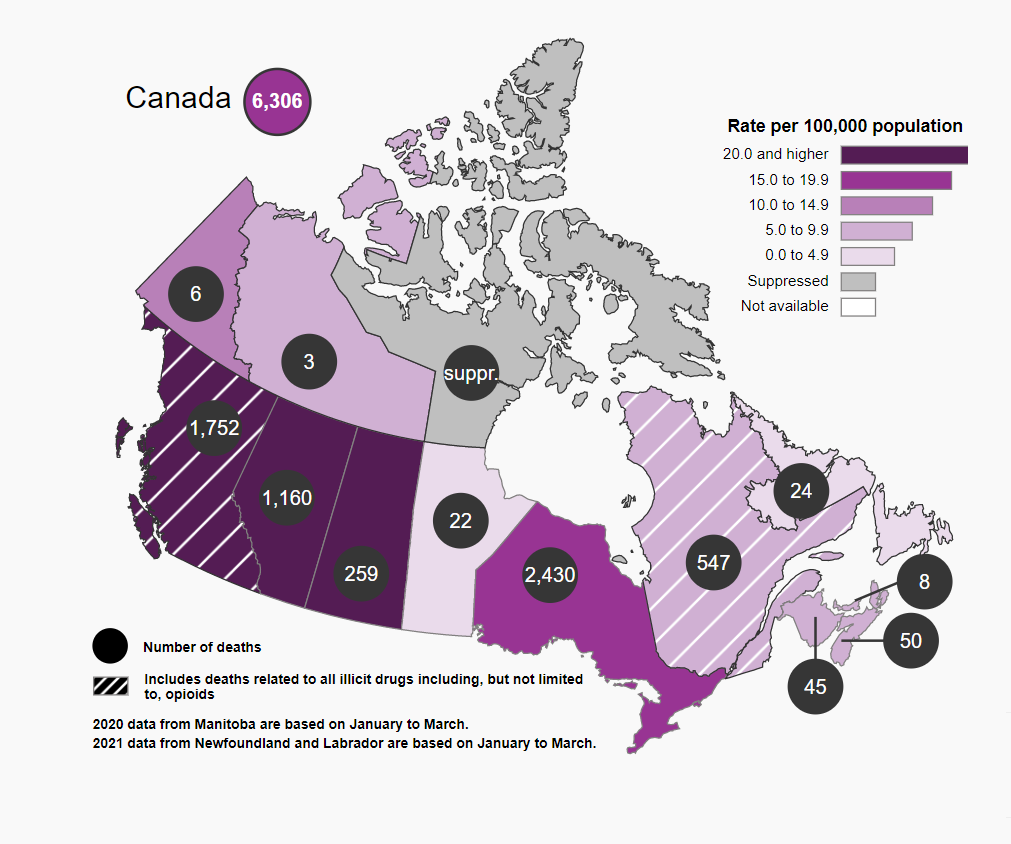

Apparent opioid toxicity deaths have not been equally distributed across the country. Western Canada has been the most affected region since 2016, although rates of opioid toxicity deaths have climbed in other parts of the country, including in Ontario. In 2020, as illustrated by Figure 2, British Columbia, Alberta and Saskatchewan experienced the highest rates of apparent opioid toxicity deaths per 100,000 population, and 85% of all apparent opioid toxicity deaths took place in British Columbia, Alberta and Ontario.13

Finally, the proportion of apparent opioid toxicity deaths involving non‑pharmaceutical substances compared to pharmaceutical products increased in 2020 over the previous two years. In 2018 and 2019, non‑pharmaceutical opioids accounted for 66% of deaths. In 2020, they accounted for 76% of apparent opioid toxicity deaths, and in the first half of 2021, 83% of deaths.14

Figure 2 – Number and Rate of Total Apparent Opioid Toxicity Deaths, by Province or Territory, 2020

Source: Government of Canada, “Maps: Number and rates (per 100,000 population) of total apparent opioid toxicity deaths by province and territory in 2020,” Opioid‑ and Stimulant‑related Harms in Canada (December 2021), Public Health Infobase, Database, accessed 1 December 2021 (select “2020” from the drop‑down menu).

There were 27,604 opioid‑related poisoning hospitalizations across Canada (excluding Quebec) between January 2016 and the first half of 2021,15 including 5,240 cases in 2020, the highest reported number since 2016.16 While opioid‑related poisoning hospitalizations outnumbered apparent opioid toxicity deaths between 2016 and 2019, in 2020, there were about 1,000 more apparent opioid‑related toxicity deaths than hospitalizations.17

Other opioid‑related hospitalizations (excluding Quebec) include 6,185 hospitalizations for adverse drug reactions from prescribed opioids and 10,082 hospitalizations for opioid use disorders between April 2018 and March 2019.18

During the first year of the COVID‑19 pandemic (April 2020 to March 2021), there were almost 32,000 Emergency Medical Services (EMS) responses to suspected opioid overdoses, based on available data from eight provinces and territories, according to the Special Advisory Committee on the Epidemic of Opioid Overdoses.19 Many regions of Canada recorded more EMS responses to suspected opioid overdoses during each quarter since the start of the pandemic than in any other quarter since the beginning of national surveillance in 2017.20

From 2016 to 2017, for the first time in decades, life expectancy at birth in Canada did not increase for either males or females. Statistics Canada determined that this stagnation was largely a result of accidental drug poisoning deaths among young adult men (particularly in British Columbia and Alberta, which saw decreases in life expectancy), which offset life expectancy gains in other areas. Opioid‑related accidental drug poisoning deaths led to a 0.11‑year (40 days) loss of life expectancy for men.21

From 2017 to 2018, female life expectancy at birth increased from 84.0 to 84.1 years, while male life expectancy at birth remained unchanged. Again, Statistics Canada reported that the stagnation in male life expectancy was a result of an increase in mortality between ages 25 and 45 years, which was “likely related” to the opioid crisis.22

The 2018 Canadian Community Health Survey estimated that 12.7% of Canadians aged 15 years and older reported prescription or non‑prescription use of pain medications containing opioids in the last year.23 Other surveys have also found that a considerable percentage of Canadians have recently used prescription opioids, although precise figures vary.24

Opioid prescribing in Canada has declined in recent years. According to the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI), the proportion of people in the study population who were prescribed opioids decreased from 14.3% to 12.3% from 2013 to 2018. In addition, during this period, fewer people started opioid therapy; fewer people were prescribed opioids on a long‑term basis; people on long‑term opioid therapy were prescribed lower doses; and more people stopped long‑term opioid therapy. The dosage and duration of therapy among people starting opioids remained relatively stable.25 These trends coincide with numerous initiatives intended to reduce the harms associated with prescription opioid use, some of which are mentioned in this HillStudy, although it is difficult to attribute these trends to any particular initiative. A revised guideline on prescribing opioids for chronic non‑cancer pain was released in 2017, but the CIHI data likely do not reflect the full impact of the new guideline because of lag time in prescriber education.26

Still, Canadians are among the world’s largest consumers of prescription opioids. The International Narcotics Control Board reported that, between 2017 and 2019, the countries reporting the highest average consumption of the main six opioid analgesics for pain management (codeine, fentanyl, hydrocodone, hydromorphone, morphine and oxycodone), were the United States, Germany, Austria, Belgium and Canada.27

Fentanyl is a very potent opioid. It can be dispensed by prescription, although other opioids are prescribed more often.28 It is also present on the illegal market, where it is frequently added to other substances such as heroin.29 Fentanyl was the most common opioid detected among drug samples seized by law enforcement and analyzed by Health Canada’s Drug Analysis Service in 2020.30

In 2016, there were more non‑fentanyl opioid deaths than fentanyl‑related opioid deaths. Since then, opioid‑related deaths involving fentanyl have become more prevalent than non‑fentanyl deaths. By 2020, there were 3.5 times more deaths involving fentanyl than those involving non‑fentanyl opioids.31

Naloxone is a drug used to temporarily reverse the effects of an opioid overdose. It can be administered by anyone who encounters an individual suspected of overdosing on an opioid. Take‑home naloxone kits are available without a prescription at most pharmacies and local health authorities in Canada.32

An environmental scan developed by the Canadian Research Initiative in Substance Misuse, released in June 2019, found that more than 590,000 publicly funded naloxone kits had been distributed across more than 8,700 distribution sites in Canada, and more than 61,000 kits had reportedly been used to reverse an overdose.33

The Canadian Substance Use Costs and Harms Working Group estimated that opioid use cost Canadians over $5.9 billion in 2017. Lost productivity accounted for the majority of these costs (over $4.2 billion), followed by criminal justice costs (over $944 million), health costs (over $438 million), and other direct costs, including research and prevention, employee assistance programs and workplace drug testing, among others (over $320 million).34

Fentanyl consumption appeared to increase in the early months of the COVID‑19 pandemic, based on a Statistics Canada analysis of data from wastewater samples from treatment plants in five cities (Halifax, Montréal, Toronto, Edmonton and Vancouver). Wastewater fentanyl loads per capita were similar to pre‑pandemic levels in April 2020, but nearly twice as high in May 2020 and close to three times higher in June and July 2020.35

Opioid‑related harms also increased during the pandemic. As stated above, there were approximately 6,306 apparent opioid toxicity deaths in Canada in 2020, representing a 71% increase over 2019 and a 43% increase over 2018 data.36 There were also 5,240 opioid‑related poisoning hospitalizations in Canada in 2020 (a 16% increase compared to 2019 and a 4% increase over 2018). In British Columbia, there were 17,011 EMS responses in 2020 (a 26% and a 27% increase over 2019 and 2018, respectively).37

In a June 2021 statement, the co‑chairs of the Special Advisory Committee on the Epidemic of Opioid Overdoses concluded that

[a] number of factors have likely contributed to a worsening of the opioid overdose crisis during the COVID‑19 pandemic in Canada, including the increasingly toxic and unpredictable drug supply; increased feelings of isolation, stress, anxiety and depression; and the limited availability or accessibility of health and social services for people who use drugs, including life‑saving harm reduction and treatment.38

A Public Health Agency of Canada simulation model released in June 2021 indicates that the number of opioid‑related deaths may remain high or even increase throughout the remainder of 2021.39

Each individual’s experience with opioids is influenced by multiple factors, including social determinants of health such as income, housing and access to health care. Some groups of people who use opioids are more likely than others to experience adverse health and social outcomes. To illustrate that the opioid crisis affects different groups of people in different ways, some statistics on opioid‑related harms disaggregated by selected identity factors are presented below.

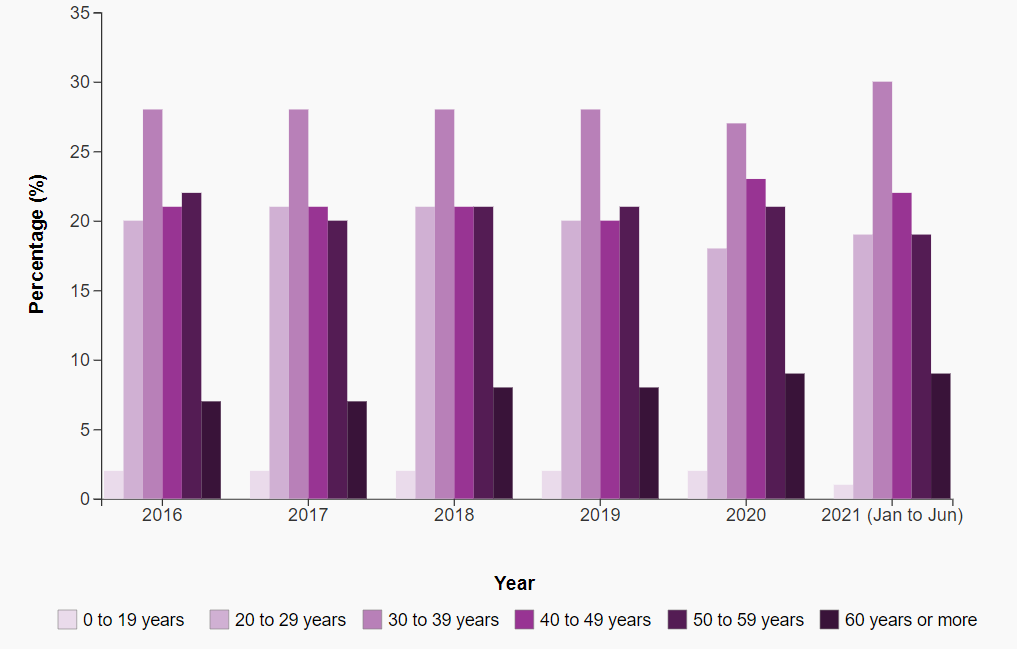

Rates of opioid‑related harms appear to differ across age groups, as shown in Figure 3. The highest proportion of accidental apparent opioid toxicity deaths since 2016 has consistently been among those individuals aged 30 to 39 years. The highest proportion of hospitalizations since 2016 has been among those people aged over 60 years each year.40

Figure 3 – Percentage of Accidental Apparent Opioid Toxicity Deaths by Age in Canada, 2016–2021 (January to June)

Note: Data for Manitoba from October 2019 to December 2020 are not included. Data for British Columbia from 2018 to 2020, and for Quebec from 2019 to 2020, include deaths related to all “illicit drugs,” which are not limited to opioids. Age data are suppressed in some provinces or territories with low numbers of cases.

Source: Government of Canada, “Graphs: Percentage of accidental apparent opioid toxicity deaths by age group in Canada, 2016 to 2021 (Jan to Jun),” Opioid‑ and Stimulant‑related Harms in Canada (December 2021), Public Health Infobase, Database, accessed 1 December 2021.

Disaggregated data reveal additional age‑based differences. For instance, in 2020, individuals aged between 30 and 39 years made up a larger proportion of accidental apparent opioid toxicity deaths involving fentanyl compared to deaths involving non‑fentanyl opioids.41

Opioid‑related data may also be disaggregated by age in combination with other identity factors, such as sex, to reveal intersectional trends.42

In 2020, 76% of people who died due to accidental apparent opioid toxicity in Canada were male, remaining almost unchanged in the first half of 2021.43 While 63% of total hospitalizations for accidental opioid‑related poisonings were among males,44 females made up 55% of hospitalizations for intentional opioid‑related poisonings in 2020.45

Sex and gender differences in accidental apparent opioid‑related deaths are not the same among all population groups in all regions. Among First Nations people in Alberta, for example, males and females were almost equally represented among accidental apparent opioid toxicity deaths from 2016 to 2018.46 However, the proportion of deaths occurring among males increased to 66% in the first six months of 2020.47

Opioid‑related behaviors and outcomes differ by gender and sex in other complex ways. For instance, people of different sexes and genders who are hospitalized for reasons related to their opioid use may also face different mental health challenges.48

Many national statistics on opioids are not disaggregated by Indigenous identity. However, available data indicate that in many parts of Canada, Indigenous communities have been disproportionately harmed by opioids. For instance:

These figures should be interpreted in the appropriate social and historical context. Many systemic factors are relevant to opioid use in First Nations, Métis and Inuit communities, including intergenerational trauma and economic inequities created by the residential school system and other forms of colonization.52 First Nations, Métis and Inuit communities also have diverse strengths and cultural resources that help to support good health. Indigenous governments and organizations have developed initiatives that take advantage of their community’s strengths to address the opioid crisis and other substance use and mental health issues.53

Health is an area of shared jurisdiction in Canada. Sections 91 and 92 of the Constitution Act, 1867 assign exclusive legislative authority over certain matters to either the federal or provincial legislatures.54 These sections list some health‑related matters (e.g., hospitals, other than marine hospitals, are a provincial matter). However, the constitution does not explicitly assign legislative power over health as a whole. As a result, health‑related measures can fall within the jurisdiction of either the federal or provincial legislatures, depending on each measure’s purpose and effect.55

Provincial legislatures have exercised their jurisdiction over health matters under sections 92(7) (hospitals), 92(13) (property and civil rights) and 92(16) (matters of a merely local or private nature) of the Constitution Act, 1867. Generally, these last two sections grant the provinces jurisdiction over health care services, the practice of medicine, the training of health professionals and the regulation of the medical profession, hospital and health insurance, and occupational health.56 Provincial and territorial governments are thus responsible for delivering most substance use prevention, treatment and harm reduction programs.

The Parliament of Canada has exercised its jurisdiction over health matters under its criminal law power (section 91(27) of the Constitution Act, 1867), its spending power (inferred from federal jurisdiction over public debt and property (section 91(1A)), and its general taxing power (section 91(3)). Federal legislation respecting opioids includes, for example, the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (CDSA) and the Food and Drugs Act. The spending power enables federal initiatives in health research, health promotion, health information, and disease prevention and control, as well as pilot projects related to provincial health initiatives.57

Additionally, the federal government directly funds or provides substance use prevention, treatment and harm reduction services to specific populations, such as First Nations and Inuit, members of the military and veterans, and people in federal prisons.58

The federal government has made investments and launched initiatives aimed at preventing and responding to opioid‑related harms.59 Some federal initiatives, for example, include efforts to restrict opioid marketing and advertising,60 a consultation on a proposal to develop new regulations for supervised consumption sites,61 and the development, in collaboration with the United States, of a Joint Action Plan on Opioids.62 The federal government has also had a series of national drug strategies since 1987; the most recent strategy was announced in 2016.63 More recently, the Government of Canada has taken some actions to support individuals who use opioids and other substances during the COVID‑19 pandemic, such as allowing provinces and territories to establish new temporary supervised consumption sites.64

Parliament has also taken steps to address the opioid crisis in recent years. In 2016, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Health studied the opioid crisis in Canada and made 38 recommendations, calling for action in the areas of national leadership, harm reduction, prescribing, treatment, mental health supports, data collection, law enforcement, border security and supports for First Nations communities.65 The federal government subsequently tabled its response to the report, in which it listed several commitments to action by federal and provincial governments, as well as stakeholder groups.66 In its response, the federal government highlighted that the Governor in Council had issued an order to amend Schedule IV of the CDSA to control certain chemicals used to produce fentanyl, which will help to interrupt the illegal supply of the substance. The response also pointed to some bills before parliament, which have subsequently come into force.

Bill C‑37, An Act to amend the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act and to make related amendments to other Acts, was introduced in December 2016 and received Royal Assent in May 2017. The bill amended the CDSA in part to simplify the application procedure for supervised consumption sites.67 As well, the federal government supported Bill C‑224, An Act to amend the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (assistance – drug overdose), also known as the Good Samaritan Drug Overdose Act, which received Royal Assent in May 2017.68 Bill C‑224 established an exemption from charges of simple possession of a controlled substance, as well as some other charges related to simple possession, for individuals who call 911 for themselves or another person experiencing an overdose, and for other people at the scene.

Several other bills related to opioid use died on the Order Paper at the dissolution of the 43rd Parliament:

Parliamentarians have also responded to the opioid crisis using other elements of the parliamentary toolkit, for example, by proposing motions, tabling petitions and asking questions in Parliament. Some of these initiatives have called on the Government of Canada to declare the opioid crisis a national public health emergency under the Emergencies Act, to develop a pan‑Canadian overdose action plan, to decriminalize simple possession and to pursue legal action against opioid manufacturers, among other measures.73

© Library of Parliament